1 Samuel 1:1–2:10 . . . Bible Study Summary with Videos and Questions

“Hannah’s Prayer Is Her Psalm”

Our first week's summary of “The Books of Samuel” ought to first provide scope to this historic account. Both books cover the period of Israel's history that's been bracketed by Samuel's conception and the end of David's reign. David turned the kingdom over to Solomon in 971 BC. David reigned for 40 and one-half years (2 Samuel 2:11; 5:5), thus he came to power in 1011 BC. Saul also reigned for 40 years (Acts 13:21), becoming king in 1051 BC. We can estimate the date of Samuel's birth fairly certainly, based on chronological references in the text, to have been about 1121 BC. Thus, the Samuel books cover the period of 1121 to 971 BC, or about 150 years of history.

First Samuel has four primary sections: (1) Hannah's story; chapter 1 to 2:21; (2) Samuel being Israel's last Judge; 2:22 to 8:22; (3) Saul, Israel's first king; 9:1 to 15:35; and (4) the decline of Saul and the rise of David; 16:1 to 31:13.

So where does the grand story of an eternal King (with a capital “K”) and his eternal kingdom begin? It starts with the desperate prayers of a heartbroken woman named Hannah. As you read about her, you might see her characteristics in yourself, not because your struggle is the same as hers, but because the feeling in your heart might resemble hers. Like Hannah, you might long for what this imperfect worldly life fails to provide; like Hannah, you likely want to be known and remembered by God. And while all your prayers to him aren't answered with a “yes,” rest assured that he hears them and knows you personally, just as he knew Hannah. First Samuel begins with a beautiful picture of a heart bowed in earnest to the Lord of all creation, asking for what only he can give.

God Uses Weak and Humble People to Do Great Things (1:1–20)

[Note: Click the link to This Week's Passage near the bottom of this page to read today's Scripture.] First Samuel begins near the end of the period that the book of Judges describes. For several hundred years, Israel had been a weak nation, without a king, without a government. Although God had established a relationship with that nation, the Israelite people were seldom loyal to God. Whenever an enemy dealt cruelly with the Israelites, they appealed to God for help; God appointed individuals to act as Israel’s leader or “judge” who'd enlist Israel’s men into an army to defeat the enemy. During each judge’s life, the people served God, but eventually began to serve false gods, again and again.

At 1 Samuel's start, we read how Hannah became a mother who'd been unable to have a child, but God miraculously gave her a son, Samuel, who became a prophet (a holy man) who appointed David to become Israel’s king. Even during the worst periods of Israel’s history, a few people remained loyal to God who'd use those people to rescue the nation and carry out his plans and purposes. Such a man was Elkanah, a godly descendant of Levi the priest, from the hill country of Ephraim. He lived when leaders of the priests, i.e., Hophni and Phinehas (Eli's sons), were behaving in a wicked manner. However, Elkanah continued to serve God most loyally.

Elkanah had two wives: Peninnah and Hannah. Peninnah had children, but Hannah had none. Every year, Elkanah, Peninnah and her children, and barren Hannah went up to Shiloh, some 20 miles north of Jerusalem where the tabernacle was stationed. Whenever the day came for Elkanah to sacrifice, he'd give portions of the meat to Peninnah and her sons and daughters; to Hannah he gave a double portion because he loved her. This very special time in Shiloh was always to be a time of rejoicing; sadness was prohibited. But for Hannah, and probably for Elkanah as well, rejoicing before the Lord was most difficult because the Lord had closed Hannah's womb. Peninnah would provoke Hannah irritatingly for years, causing her to cry (vv. 4–8).

As we see in vv. 9–11, Hannah desired a son so much that she made an extraordinary promise to God: If God would give her a son, she'd not keep that boy for herself but would give him to God so that he'd become a Nazirite for his whole life.

Nazirites were those people who made a personal promise to God by obeying a number of special rules (see Numbers 6): A Nazirite wouldn't cut his hair, wouldn't eat grapes or drink grape juice or alcohol, and couldn't go near a dead body or attend a funeral, even one for a family member. Usually, people became Nazirites for a certain period of time, perhaps for only a few months, sometimes for many years, but Hannah prayed to God, asking him that, if he'd give her a son, she'd allow him to become a Nazirite servant all his life (v. 11).

Eli, Israel’s chief priest, was an old, weak man. In fact, he was weak in many different ways: His eyes were weak (3:2); his legs were probably weak (1:9); he was too weak to prevent his sons from behaving wickedly (3:13); and, although he genuinely served God, his personal relationship with God seemed weak (2:29).

On this particular trip to Shiloh, Hannah barely made it through the meal. Somehow she fortified herself against Peninnah’s cruel remarks and actions. But after eating and drinking, she hurried off to find her way to the tabernacle where she poured out her soul to God. Inside, she prayed silently as Eli the priest, sitting by the doorway, looked on with interest. Seeing her shoulders heaving as she sobbed in great distress, weeping bitterly (v. 10), but not hearing her words, Eli jumped to the wrong conclusion, assuming that she'd been celebrating too much and that her happiness amounted to drunkenness, for which he rebuked her. So he instructed her to stop such excess drinking (vv. 13–14).

Hannah quickly yet tearfully assured Eli that she wasn't drunk but was pouring out her soul before the Lord. She begged him not to condemn her as being a worthless woman (vv. 15–16). Among those words that Hannah sobbed out to God was a vow promising God that if he'd grant her a son, she'd give that son back to Him as a Nazirite (v. 11). Priest Eli assured Hannah that God would grant her petition and bless her (v. 17). From that moment on, Hannah was able to enter the worship celebration and eat the meal; her face soon radiated with joy rather than sorrow.

Rising early, they worshiped the Lord before making their way back home to Ramah. Some time later, Hannah conceived and bore the promised child whom she named "Samuel" (a surname of Hebrew origin meaning either "name of God" or "God has heard"). She knew that he was the child for whom she asked the Lord, and that he was the answer to her prayer (v. 20). The name Samuel is a constant reminder of this child’s origin and destiny.

Hannah Dedicates Samuel to God (vv. 21–28)

While the child was still nursing, it became time for the family to make its yearly trek to Shiloh for the annual sacrifice. Elkanah went up with the rest of his family, but Hannah remained behind. She wasn't trying to avoid keeping her vow (vv. 21–23). Quite the contrary! She wanted to stay home to wean the child for a year, then take Samuel with her when it was time for the next journey to Shiloh.

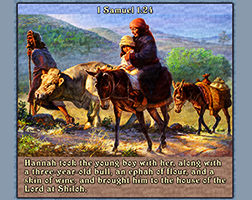

Eventually the child was weaned. Hannah would then take and leave little Samuel in Shiloh with Eli. The three-year-old bull they took with them was slaughtered and brought to Eli. Hannah reminded him that she was the woman who stood beside him, praying so fervently that he assured her that God would grant her petition. She also told him that, to fulfill her vow, she'd brought her child so she could give him to the Lord. Shortly, she'd leave Samuel behind under Eli's care. Before leaving, she reiterated her prayer offer that praised the Lord; a prayer for which Hannah will be long-remembered.

Hannah’s Prayer Is a Psalm (2:1–10)

Hannah’s prayer is one of a series of important songs and prayers by women in the Bible. Others include Miriam’s song (Exodus 15:20–21), Deborah’s song with Barak (Judges chapter 5), and Mary’s song (Luke 1:46–55).

In vv. 1–10, Hannah speaks using a number of features worth noting. Why not read it now before we look closely at its seven elements. . .

• First, Hannah’s prayer is a psalm. Several translations indicate this by the way they format text. It resembles a psalm from the book of Psalms. Hannah’s prayer employs parallelism and symbolism, which are typical of psalms.

• Second, Hannah’s psalm is a prayer of praise, one that Hannah may have prepared in advance for her worship. It's a prayer addressed to God, a prayer of praise and thanksgiving.

• Third, Hannah’s psalm is now a part of Scripture. No longer a private work of hers, it's a permanent part of the Holy Scriptures for all of us to read.

• Fourth, Hannah’s psalm is therefore an inspired psalm. “All Scripture is inspired by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, for training in righteousness;…” (2 Timothy 3:16). Since this psalm is a part of the Holy Scriptures, we know that it's inspired by God through the Holy Spirit (see 1 Corinthians 2:10–13 and 2 Peter 1:21). Are Hannah’s words beyond her own natural capacity to articulate? Indeed they are! So are the words of every inspired author of Scripture. This is precisely why we can easily accept that Hannah penned this psalm through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit.

• Fifth, Hannah’s psalm appears to reflect Israel’s experiences with God in the past. Her words of praise in her psalm seem to flow, in part, from Israel’s past experiences, particularly its exodus.

• Sixth, Hannah’s prayer goes far beyond her own experience, focusing on the character of the one true God whom she worships and praises; it doesn't concentrate on her sorrow, her suffering, or even on her blessings; it focuses on her God! Out of her suffering and exaltation, she sees God more clearly; as a result, she praises him for who and what he is: holy (v. 2); faithful (“Rock,” v. 2); all-knowing (v. 3); all-powerful (v. 6); gracious (v. 8); a sovereign reverser of circumstances (vv. 6–10). God is quite apparent in these few verses!

• Seventh, Hannah’s prayer goes far beyond her experience, beyond the past and present; it looks far ahead to the future. It’s prophetic, looking forward to the time when Israel would have a king (v. 10), albeit the ultimate King, our Lord Jesus Christ, who's the ultimate fulfillment of Hannah's messianic prophecy.

Let's not fail to realize and appreciate this: While Hannah’s psalm is the expression of her great joy and praise, it was offered when she had to leave her son behind, never again to have him in her home. It was at that time when Hannah expressed her joy and gratitude to God for answering her prayer, a time when Hannah expressed her faith in God and her devotion to him, a time of separation when she'd leave Samuel in Shiloh to return to Ramah. God’s faithfulness in the past was her assurance of his future faithfulness, and so she gave her child to God.

Closing considerations Hannah’s psalm couldn't have been written without the suffering that preceded it. It was God who closed Hannah’s womb; it was God who planned for her to suffer at the hand of her cruel counterpart, Peninnah; it was God who orchestrated the many painful and pleasant events in Hannah’s life, such that her resulting psalm could become the masterpiece it is. That's the way God employs the human and divine elements in the writing of all his Scriptures.

It's God who orchestrates the background of your lives to uniquely prepare and equip you for the ministry he assigns you. Never see your past difficulties as hindrances to the present or the future. Instead, make a hearty effort to allow today's text to give you a heartwarming picture of God, bringing about his plans and blessings in your life. Doing so, he'll manifest his grace upon you during your sorrow, suffering, and human weakness.

† Summary of 1 Samuel 1:1–2:10

The opening of 1 Samuel introduces Hannah, a woman deeply distressed by her inability to have children and by the taunts of her husband’s other wife, Peninnah. Though burdened and in anguish, Hannah persistently seeks God in prayer at the sanctuary in Shiloh, vowing that if God gives her a son, she’ll dedicate him to the Lord’s service for life. Initially misunderstood by the priest Eli, who mistakes her heartfelt, silent prayers for drunkenness, Hannah’s sincerity is eventually affirmed. Then Eli blesses her. God answers Hannah’s plea — she gives birth to Samuel, names him as a testimony to God’s faithfulness, and after weaning him, fulfills her vow by bringing him to serve before the Lord in Shiloh.

In gratitude and worship, Hannah offers a profound prayer (2:1–10), expressing both personal joy and deep theological insight. Her song proclaims God’s holiness, power, and faithfulness, while highlighting themes that echo throughout the rest of Samuel: the Lord reverses human fortunes, exalts the humble, and brings down the proud. Hannah’s prayer is striking for its prophetic tone, anticipating God’s future provision of a king and his ultimate anointed one. It declares that God is sovereign over life and death, poverty, and wealth, and will ultimately give strength to his king and exalt his anointed — a foreshadowing of both Israel’s monarchy and the coming Messiah. Together, Hannah’s story and song lay a foundation of faith, hope, and God’s active involvement in human history.

Key points with verse references:

Hannah’s Barrenness and Prayerful Faith (1:1–11): Hannah is deeply grieved by her inability to have children and by taunting from Peninnah. In her distress, she prays fervently at Shiloh, vowing that if God grants her a son, she will dedicate him to the Lord for his whole life (1:10–11).

God Answers and Samuel’s Birth (1:12–20): Initially mistaken for being drunk by priest Eli (1:12–14), Hannah explains her anguish and faith. Eli blesses her (v. 17), and God grants her request; she gives birth to Samuel, acknowledging God’s answer to her prayers (vv. 19–20).

Hannah Fulfills Her Vow (1:21–28): True to her promise, Hannah brings young Samuel to the tabernacle at Shiloh after he is weaned. She presents him to Eli, declaring her faithfulness to her vow and dedicates Samuel to lifelong service before the Lord (vv. 24–28).

Hannah’s Song of Praise (2:1–10): With a grateful heart, Hannah offers a prophetic song exalting God’s holiness, power, and justice. Her prayer proclaims that God reverses fortunes, exalts the humble, and brings down the proud (2:1–8). She closes with a vision of God giving strength to his king and exalting his anointed (2:10), foreshadowing future deliverance and messianic hope.

Theological Themes Throughout: This passage highlights God’s sovereignty in answering prayer, his concern for the lowly, and his ultimate plan to provide a king and deliverer for his people (1:9–2:10).

This Week's Passage

1 Samuel 1:1–2:10

New International Version (NIV) [View it in a different version by clicking here; also listen to chapter 1 and listen to chapter 2 narrated by Max McLean.]

† Summary Video: “The First Book of Samuel”

† Watch this introductory video clip created by BibleProject on bibleproject.com.

- Q. 1 How does this account in chapter 1 illustrate the evils of polygamy?

- Q. 2 Exactly what in v. 11 did Hannah imply when she said, “I will give him to the Lord”?

- Q. 3 In Hannah's prayer/psalm, who were her enemies? How did she prevail over them?