The Art World Commemorates Peter

— Album 4 of 17 Photo Albums —

Warren Camp’s presentation of 550 famous “Peter” works of art includes historic paintings, frescoes, stained glass, etchings, sculptures, engravings, and other artwork monuments. They come from the Gothic (1100–1400), High Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, Neoclassical, and Romantic (1800s) eras.

All are popular works, designed and created by celebrated artists, many of whom you’ll likely recognize, including Rembrandt, Raphael, Michelangelo, El Greco, Da Vinci, Masaccio, Huret, Galle, Tissot, Botticelli, Dürer, Rubens, and many more. They’ll bring back recollections of your “Art History 101” classes, using Janson’s History of Art textbook.

Whether depicting “Cephas,” “Petrus,” “Simon,” “Simeon,” “Simon Bar-Jonah,” “Simon Peter,” “The Rock,” “Peter,” “Apostle Peter,” or “Saint Peter,” the enlarged images of this acclaimed Bible figure come with factual and enlightening details: the artist’s bio; when each work was created; where it can be seen; applicable Bible passages; background and highlights of each work; and photo sources with copyright notices.

To appreciate the impact that Peter had on numerous art-world masters, be sure to click each thumbnail to enlarge it.

• These photo albums complement the Bible-study commentaries Warren has written for “1st and 2nd Peter,” found here.

…

Album 1 (Peter, alone) | Album 2 | Album 3 | Album 4 | Album 5

Album 6 | Album 7 | Album 8 | Album 9 | Album 10 | Album 11

Album 12 | Album 13 | Album 14 | Album 15 | Album 16 | Album 17

Album topics are shown at the [ ⇓ bottom ⇓ ] of each page.

Christ Gives Peter the Keys to Heaven

to Saint Peter”

Slide 1

Click to enlarge.

Rubens — c. 1612–1614

oil on oak panel

Keys to Saint Peter”

Slide 3

Click to enlarge.

Castello — 1598

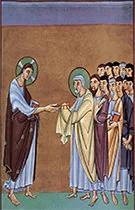

illumination on vellum

Keys to Saint Peter”

Slide 5

Click to enlarge.

Bolognini — 1640–1670

etched print

Receives the Keys”

Slide 6

Click to enlarge.

Ottonian artists

early 11th century

color on parchment

Keys to Saint Peter”

Slide 7

Click to enlarge.

German Romanesque

c. 1150–1200

elephant ivory carving

Slide 10

Click to enlarge.

Vincenzo Catena, c. 1525, oil on canvas

Saints Peter and Paul”

Slide 11

Click to enlarge.

Moretto — c. 1540

oil on canvas

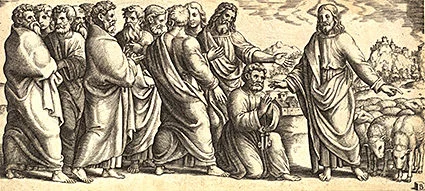

Slide 12

Click to enlarge.

Master of the Die, 1530–1560, engraved print

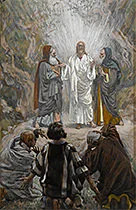

The Transfiguration

(Matthew 17:1–6; Mark 9:2–7; Luke9:28–36)

Slide 20 — Click to enlarge and read its detailed caption.

Peter Paul Rubens, 1605, oil on canvas

Tribute Money #1: The Temple Tax and the Fish (Matthew 17:24–27)

Slide 28 — Click to enlarge and read its detailed caption.

Note the detailed triptych, below, of this “Tribute Money” masterpiece.

» Watch this descriptive video that highlights Masaccio’s intent, styles, and techniques.

Tribute Money #2: Payment to Caesar (Matthew 22:15–22)

Slide 32

Click to enlarge.

James Tissot — 1886–1894

opaque watercolor over graphite on gray wove paper

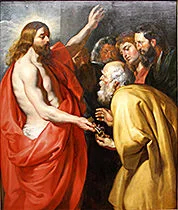

- 1. “Christ Giving the Keys of Heaven to St Peter,” oil on oak panel, painted by Peter Paul Rubens, c. 1612–1614

“Christ Giving the Keys to St Peter” This painting by the Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens, “completed in 1614, is now in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. The painting was probably produced between 1612 and 1614 to fulfill a commission by the Kapellekerk in Brussels for a painting to decorate the tomb of Peter Bruegel the Elder, showing his name saint (i.e., Peter). This commission was probably set up by David Teniers the Younger, the son-in-law of Jan Brueghel the Elder; he may even have been involved in its production.”[1]

“The gospel passage that inspired Rubens to paint this (Matthew 16:13–20) describes a conversation between Jesus and his disciples regarding his identity. He first asks them who people say he is; he then asks who the disciples say he is. Peter immediately and boldly declares, Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God. In response, Jesus says that Peter’s declaration of faith [not Peter himself] will be the rock upon which the Lord will build his church.

“Jesus describes the authority that he’s delegated to them as the ‘keys to the kingdom of heaven.’ Peter and the rest of the apostles were assigned a crucial role in introducing the gospel to the world. In Christ’s name, they’ll declare that he is the Messiah and that faith in him allows the only entrance into his heavenly kingdom. In his name, they’ll also exercise discipline within the church, setting the standard for both what’s true and how that truth will be practiced. When the apostles declare something bound or loosed[2] in Jesus’ name, the power that resides in heaven will respond and make it so.”[3]

… Height:71.8 in. (182.6 cm), width: 62.5 in. (159 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: © José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

… See eight additional Rubens’ oil paintings in our “Peter Masterpieces” albums: Album 4 (5@); 5; 9; and 16.

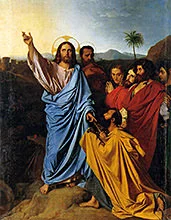

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 2. “Jesus Delivering the Keys to Saint Peter,” oil on canvas, painted by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1820

This large Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres painting depicts the scene of Christ delivering the keys of the kingdom of heaven to Peter. This exchange of heaven’s keys occurs in the presence of other haloed apostles. “Ingres’ impressive study is of Christ, the central figure in one of the artist’s most important early religious paintings: ‘Jesus Delivering the Keys to Saint Peter.’ The painting was originally to have been frescoed, but was eventually executed in oil on canvas. “Completed in 1820, Ingres always regarded it as one of his masterpieces: ‘This is my best work,’ he wrote to a friend in 1819.”[1]

“Jesus describes the authority that he’s delegated to them as the ‘keys to the kingdom of heaven.’ Peter and the rest of the apostles were assigned a crucial role in introducing the gospel to the world. In Christ’s name, they’ll declare that he is the Messiah and that faith in him allows the only entrance into his heavenly kingdom. In his name, they’ll also exercise discipline within the church, setting the standard for both what’s true and how that truth will be practiced. When the apostles declare something bound or loosed[2] in Jesus’ name, the power that resides in heaven will respond and make it so.”[3]

“The gospel passage that inspired Ingres to paint this work, Matthew 16:13–20, describes a conversation between Jesus and his disciples regarding his identity. Jesus first asks them who people say he is; he then asks who the disciples say he is. Peter immediately and boldly declares that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God. In response, Jesus says that Peter’s declaration of faith will be the rock upon which the Lord will build his church.

… Height: 110.2 in. (280 cm), width: 85.4 in. (217 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 3. “Christ Giving the Keys to St Peter,” illumination on parchment, created by Giovanni Battista Castello, 1598

“Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter” “In front of ruined monuments of ancient Rome — the Temple of Minerva, Trajan’s Column — Christ consigns the keys of the kingdom of heaven to Saint Peter. This painting, formerly attributed to Giulio Clovio, may refer to a project designed by Michelangelo, c. 1542, for the Cappella Paolina in the Vatican, but never executed.”[1] [On view at the Louvre.] Giovanni Battista Castello (1547–1637, known as Il Genovese) was an Italian illuminator and goldsmith, part of a family of artists active in Genoa. His works, often incorporated into prized reliquaries and portable altars, were prized by European monarchs and aristocrats as adornments for their personal chapels.

“The biblical passage that makes reference to the ‘keys of the kingdom’ is Matthew 16:19. Jesus had asked His disciples who people thought He was. After hearing several of the more popular opinions, Jesus aimed His question directly at His disciples. Peter, responding for the twelve, acknowledged Jesus as the Christ, the Son of the Living God. After this great confession, Jesus replied, ‘Blessed are you, Simon Bar-Jonah! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father who is in heaven. And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven’ (vv. 17–19).[2]

… Height:12.7 ft. (384 cm), width: 9.7 ft. (292 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Bernardo Castello, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

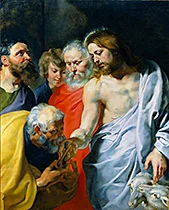

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 4. “Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter,” oil on oak panel, painted by Peter Paul Rubens, c. 1616

Peter Paul Rubens’ “Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter” “In this altarpiece, Flemish artist Rubens combines an episode from John’s gospel — when Christ asked his disciple Peter to “Feed my Sheep” — with the account in Matthew’s gospel of Christ’s promise to present Peter with the keys of the kingdom of heaven. The combination of subjects was rare, though it had been used by Raphael in Saint Peter’s Sistine Chapel Tapestries.”[1]

We see that the text of Matthew 16:13–20 “inspired Rubens to paint this work. It describes a conversation between Jesus and his disciples regarding his identity. Jesus first asks them who people say he is; he then asks who the disciples say he is. Peter immediately and boldly declares that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God. In response, Jesus says that Peter’s declaration of faith [not Peter himself] will be the rock upon which the Lord will build his church. Jesus describes the authority that he’s delegated to them as the ‘keys to the kingdom of heaven.’ Peter and the rest of the apostles were assigned a crucial role in introducing the gospel to the world. In Christ’s name, they’ll declare that he is the Messiah and that faith in him allows the only entrance into his heavenly kingdom. In his name, they’ll also exercise discipline within the church, setting the standard for both what’s true and how that truth will be practiced. When the apostles declare something bound or loosed[2] in Jesus’ name, the power that resides in heaven will respond and make it so.”[3]

… Height: 54.8 in. (139.2 cm), width: 45.1 in. (114.8 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Peter Paul Rubens, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

… See eight additional Rubens’ oil paintings in our “Peter Masterpieces” albums: Album 4 (5@); #5; 9; and 16.

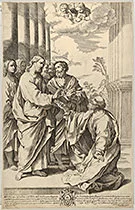

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 5. “Christ Giving the Keys of the Church to St Peter Who Kneels Before Him,” etched print by Gian Bolognini, 1640–1670

Giovanni Battista Bolognini (1611–1688) was an Italian painter and engraver of the Baroque. He was a pupil of Guido Reni from whom this etching is derived [see slide 8]. This is his “Christ Giving the Keys of the Church to Saint Peter Who Kneels Before Him” etching.

Keys One easy identifier of Apostle Peter in Christian art has been a set of large keys in his possession, as was biblically presented by Jesus: “I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven”[1] (Matthew 16:19). But that symbolic language of Jesus isn’t the first time that the purpose of keys is mentioned in the Bible. We find an initial reference in the text of Prophet Isaiah’s book, often called the “Isaiah 22:22 key.” But you could also call it the “Revelation 3:7 key” because this prophetic Scripture is mentioned in both books, as follows.

Isaiah 22:22 reads: “I will place on his shoulder the key to the house of David; what he opens no one can shut, and what he shuts no one can open.” And Revelation 3:7 reads: “To the angel of the church in Philadelphia write: These are the words of him who is holy and true, who holds the key of David. What he opens no one can shut, and what he shuts no one can open.” Note: The “he” in 3:7 refers of course to Jesus who holds the key that can open and shut as he chooses. When he opens a door, no man or woman can shut it; when he shuts a door, no one can open it. Believers in Jesus are to discern his will and kingdom purpose so we can exercise our authority in his name to be able to open what he wants opened and shut what he wants shut.

… Height: 19 5/8 in. (49.9 cm), width: 12 1/2 in. (31.7 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: The Met; Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1926

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 6. “The Pericopes of Henry II: Saint Peter Receives the Keys,” color on parchment, by Ottonian artists, early 11th century

Saint Peter Receives the Keys “The Pericopes of Henry II is the most beautiful and extreme expression of the aesthetics of the Liuthar Group, a twenty-four-page collection of manuscripts that was created between 990 and 1015 in the famous scriptorium of Reichenau Abbey. Emperor Heinrich II (973–1024), the only canonized German monarch, commissioned numerous luxury biblical manuscripts, a sign not only of his personal piety, but also of the close connection between his imperial administration and the church. This large-format manuscript is characterized by hundreds of large gold initials and miniature pages with a brilliantly polished gold background, some of the first to be created in Western book illumination.

“In contrast to a normal gospel book, a pericope book contains only the specific gospel passages to be read during mass; it is arranged according to the liturgical year to make it easier to find the correct passage. The Pericope Book of Henry II is one of the last and most outstanding examples of Ottonian book illumination. This is a great medieval manuscript in every way!”[1] The large format and lush gold surfaces radiate grandeur and solemnity. See rare closeups of this masterpiece of Ottonian illumination.

In this colored illuminated manuscript, Jesus [left] hands haloed Peter the key to the kingdom of heaven. The biblical passage that makes reference to the “keys of the kingdom” is Matthew 16:19. Jesus had asked his disciples who people thought he was. See Peter’s answer here.

… Height: 10.4 in. (26.5 cm), width: 7.5 in. (19.2 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons: The Yorck Project (2002)

… The artists’ short history and collections

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 7. “Plaque: Christ Presenting the Keys to Saint Peter and the Law to Saint Paul,” German ivory carving, 1150–1200

“The theme of ‘Christ Handing the Keys of Heaven to Saint Peter and the Law to Saint Paul,’ which originated in fourth-century Rome, refers to the Gospel of Matthew (16:18): ‘I also tell you that you are Peter and on this rock I will build my church.’ At the same time, it highlights the importance of Saint Paul’s mission to the non-Jewish Gentiles. In this powerful interpretation, a domed structure, perhaps representing the heavenly Jerusalem, replaces the rock on which Christ is depicted more frequently. The dramatic expressions, the fluid clinging drapery, and the openwork carving are characteristic of German Romanesque ivory carving. The inscription, including the date 1200, is of later origin.”[1]

“The German artist who carved this ivory plaque was inspired by Matthew 16:13–20. That gospel passage describes a conversation between Jesus and his disciples regarding his identity. Jesus first asks them who people say he is; he then asks who the disciples say he is. Peter immediately and boldly declares that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God. In response, Jesus says that Peter’s declaration of faith will be the rock upon which the Lord will build his church.

“Jesus describes the authority that he’s delegated to them as the ‘keys to the kingdom of heaven.’ Peter and the rest of the apostles were assigned a crucial role in introducing the gospel to the world. In Christ’s name, they’ll declare that he is the Messiah and that faith in him allows the only entrance into his heavenly kingdom. In his name, they’ll also exercise discipline within the church, setting the standard for both what’s true and how that truth will be practiced. When the apostles declare something bound or loosed[2] in Jesus’ name, the power that resides in heaven will respond and make it so.”[3]

… Height: 5 15/16 in. (15.1 cm), width: 3 3/8 in. (8.5 cm), thickness: 3/8 in. (0.9 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: The Met: The Cloisters Collection, 1979

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 8. “Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter,” oil on canvas, painted by Guido Reni, 1625

Guido Reni (1575–1642) was an Italian painter of the Baroque period, although his works showed a classical manner, similar to Simon Vouet, Nicholas Poussin, and Philippe de Champaigne. He painted primarily religious works.[1] This “Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter” painting is currently on display at the Louvre.

“The biblical passage that makes reference to the ‘keys of the kingdom’ is Matthew 16:19. Keys are used to lock or unlock doors. The specific doors Jesus has in mind in this passage are the doors to the Kingdom of Heaven. Jesus is laying the foundation of His church (Ephesians 2:20). The disciples will be the leaders of this new institution, and Jesus is giving them the authority to, as it were, open the doors to heaven and invite the world to enter. As the apostles preached the gospel, those who responded in faith and repentance were granted access to the Kingdom of Heaven; yet those who continued to harden their hearts and reject the gospel of God’s saving grace were shut out of the Kingdom.

“God’s will is that sinners be granted access to heaven through the righteousness of Christ. Consider Jesus’ warning to the Pharisees: ‘But woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you shut the kingdom of heaven in people’s faces. For you neither enter yourselves nor allow those who would enter to go in’ (Matt. 23:13). If the gospel message is distorted or ignored, or if unrepentant sin is not adequately disciplined, the doors to the Kingdom of Heaven are being shut in people’s faces.”[2]

… Height:11.2 ft. (343 cm), width: 7.2 ft. (218 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Guido Reni, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 9. “Christ’s Charge to Peter,” cartoon for a drapery, painted by Raphael, 1515–1516

Christ’s Charge to Peter “This is one of the Raphael Cartoons, designed for tapestries and commissioned by Pope Leo X in 1513. Painted by Raphael (1483–1520) and his assistants, the tapestries were full-scale designs for draperies to be hung in the Sistine Chapel in Rome. They illustrated scenes from the lives of Saint Peter and Saint Paul who were seen as founders of the Christian Church. The scene here combines two different events described in the Bible, before and after Jesus’ resurrection: (1) when Christ charged Peter with the care of the faithful, symbolized by the sheep (Matthew 16:18–19), and (2) when he gave him the keys to the gates of heaven (John 21:15–17).”[1]

“In both the Old and New Testaments, keys symbolize power and authority. The nature of that power and authority varies depending on the context. Isaiah 22:22 refers to ‘the key of the house of David,’ which refers to the authority of the steward who manages the household of the king. That same imagery is applied to the risen Christ (Revelation 3:7), who also has ‘the keys of Death and Hades’ (Rev. 1:18). In Luke 11:52, Jesus claims that the experts in the Jewish Law ‘have taken away the key of knowledge.’ In other words, through their hypocrisy, they’ve not only failed to enter the kingdom of God themselves, but have prevented others from entering as well. Through Peter’s faithful proclamation of the gospel [not through Peter himself], he and all devoted disciples of Jesus will open the door of the kingdom of heaven to those who respond in faith, while at the same time keeping it shut from those who do not.”[2]

… Height:11.3 ft. (345 cm), width: 17.6 ft. (535 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, and image enlargement: Wikimedia Commons; Victoria & Albert Museum, London, lent by Her Majesty The Queen

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 10. “Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter,” oil on canvas, painted by Vincenzo Catena, c. 1525

Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter “Vincenzo Catena (c.1480–1531), also known as Vincenzo de Biagio, was an Italian painter of the Renaissance Venetian school. His early style is closer to that of Giovanni Bellini than the innovative work of Giorgione. It wasn’t until a few years after Giorgione’s death in 1510 that his influence began to show itself in Catena’s output. There are about a dozen signed paintings by Catena in existence; only one of them (‘The Martyrdom of St Christina’ [1520] in Santa Maria Mater Domini Church in Venice) can be dated with any certainty.”[1]

“It was the gospel passage of Matthew 16:13–20 that inspired Catena to paint this oil-on-panel work, describing a conversation between Jesus and his disciples regarding his identity. Jesus first asks them who people say he is; he then asks who the disciples say he is. Peter immediately and boldly declares that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God. In response, Jesus says that Peter’s declaration of faith will be the rock upon which the Lord will build his church.

“Jesus describes the authority that he’s delegated to them as the ‘keys to the kingdom of heaven.’ Peter and the rest of the apostles were assigned a crucial role in introducing the gospel to the world. In Christ’s name, they’ll declare that he is the Messiah and that faith in Christ allows the only entrance into his heavenly kingdom. In his name, they’ll also exercise discipline within the church, setting the standard for both what’s true and how that truth will be practiced. When the apostles declare something bound or loosed[2] in Jesus’ name, the power that resides in heaven will respond and make it so.”[3]

… Height: 33.9 in. (86 cm), width: 53.1 in. (135 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Museo Nacional del Prado; Royal Collection

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 11. “Christ in Glory with Saints Peter and Paul,” oil on canvas, painted by Moretto da Brescia, c. 1540

Christ in Glory with Saint Peter and Saint Paul “is an oil-on-canvas painting by Moretto da Brescia, executed c. 1540, displayed on the altar dedicated to St Peter, in the abbey church of San Nicola in Rodengo-Saiano, where it has been since its production. It shows Christ handing the keys of the kingdom to Peter and the book of doctrine to Paul of Tarsus.”[1]

From the start, we learn in John 1:15 that “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth.” In Moretto’s altarpiece painting, what stands out is a disregard for historical accuracy. Christ Jesus had, while he lived on the earth, given Peter [left] the symbolic keys to the kingdom of heaven (Matthew 16:13–20). Also while on earth, Christ, in his glory, enabled Paul [right] to powerfully resist persecution (hence the symbolic sword) so he could write many New Testament epistles. Yet, Moretto chose to present the glorified Christ Jesus as the ascended Lord, reaching down from his heavenly abode, connecting with both of his devoted apostles.

Nevertheless, this painted image is accurate: Moretto effectively documents Peter and Paul as having devoted their lives to sharing the great news about Jesus Christ who’d entered the world and changed it forever. Surely, Peter and Paul were flawed individuals. Among the greatest faith-declaration stories is that of Peter’s three-time denial of Jesus, shown in our Album 15. We also remember that “Saul was still breathing out murderous threats against the Lord’s disciples” (Acts 9:1). It was in Christ’s glory that both were granted the grace to repent and become ardent servants and followers of Lord Jesus.

… Height: 88.5 in. (225 cm), width: 49.2 in. (125 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Moretto da Brescia, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album.

- 12. “The Delivery of the Keys to Saint Peter,” engraved print by Master of the Die, 1530–1560

“Master of the Die was an Italian engraver and printmaker whose identity is unknown. He was given this name because he signed his prints with a small die. What is known is that the Master of the Die studied under Marcantonio Raimondi, working in the style of Raphael. Some of his works reside at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.”[1]

The gospel passage that inspired the Master of the Die to engrave this work, Matthew 16:13–20, describes a conversation between Jesus and his disciples regarding his identity. Jesus first asks them who people say he is; he then asks who the disciples say he is. Peter immediately and boldly declares that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God. In response, Jesus says that Peter’s declaration of faith [not Peter himself] will be the rock upon which the Lord will build his church.

“Jesus describes the authority that he’s delegated to them as the ‘keys to the kingdom of heaven.’ Peter and the rest of the apostles were assigned a crucial role in introducing the gospel to the world. In Christ’s name, they’ll declare that he is the Messiah and that faith in him allows the only entrance into his heavenly kingdom. In his name, they’ll also exercise discipline within the church, setting the standard for both what’s true and how that truth will be practiced. When the apostles declare something bound or loosed[2] in Jesus’ name, the power that resides in heaven will respond and make it so.”[3]

… Height: 4 15/16 in. (12.5 cm), width: 10 5/8 in. (27 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, and image enlargement: The Met; The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1949

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 13. “Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter,” oil on altarpiece panel, painted by Lorenzo Veneziano, 1369

Lorenzo Veneziano “fulfilled countless commissions in Venice and its vicinity that display a handsome fusion of Byzantine and later pictorial currents. His commissions included an altarpiece which was later dismembered. This central panel depicting ‘Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter’ is now in the Museo Correr, Venice; the side panels were destroyed in Berlin in 1945. The five surviving predella panels are the ‘Conversion of Paul,’ ‘Calling Apostles Peter and Andrew’ (Album 2), ‘Christ Rescuing Peter from Drowning’ (Album 3), ‘Apostle Peter Preaching’ (Album 2), and ‘Crucifixion of Peter’ (Album 16). In this central panel, the date and signature are legible under the throne’s base; dated 1369 by the Venetian calendar of the day (that is, 1370[1)].”[2]

“Veneziano was inspired by Matthew 16:13–20 to paint this online-on-altarpiece. The gospel passage describes a conversation between Jesus and his disciples regarding his identity. Jesus first asks them who people say he is; he then asks who the disciples say he is. Peter immediately and boldly declares that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God. In response, Jesus says that Peter’s declaration of faith will be the rock upon which the Lord will build his church.

“Jesus describes the authority that he’s delegated to them as the ‘keys to the kingdom of heaven.’ Peter and the rest of the apostles were assigned a crucial role in introducing the gospel to the world. In Christ’s name, they’ll declare that he is the Messiah and that faith in Jesus allows the only entrance into his heavenly kingdom. In his name, they’ll also exercise discipline within the church, setting the standard for both what’s true and how that truth will be practiced. When the apostles declare something bound or loosed[2] in Jesus’ name, the power that resides in heaven will respond and make it so.”[3]

… Height: 35.4 in. (90 cm), width: 23.6 in. (60 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Lorenzo Veneziano, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album.

- 14. “The Sacrament of Ordination (Christ Presenting the Keys to St Peter),” oil on canvas, by Nicolas Poussin, 1636–1640

Nicolas Poussin’s “The Sacrament of Ordination is from one of the most celebrated groups of paintings in the entire history of art. The set depicting each of the Seven Sacraments (first series) was commissioned from Poussin (1594–1665) by Cardinal Francesco Barberini. To illustrate ordination, Poussin depicted the gospel account of Christ giving the keys of heaven’s kingdom to the kneeling apostle, Peter. Poussin infused emotional power to convey the varied gestures and expressions of each apostle. The far-right figure, with his face obscured in shadow, is Judas Iscariot, who’d betray Christ.”[1]

It’s Matthew 16:13–20 that “inspired Nicolas Poussin to paint this oil-on-canvas work, describing a conversation between Jesus and his disciples regarding his identity. Jesus first asks them who people say he is; he then asks who the disciples say he is. Peter immediately and boldly declares that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God. In response, Jesus says that Peter’s declaration of faith [not Peter himself] will be the rock upon which the Lord will build his church.

After Jesus had declared that he’d build his church on the truth of Peter’s noble confession, he told Peter, “I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” (Matt. 16:19). Later, addressing all the disciples, Lord Jesus repeated the words, “Whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven” (18:18). When the apostles declare something bound or loosed[2] in Jesus’ name, the power that resides in heaven will respond and make it so.”[3]

… Height: 37 3/4 in. (95.9 cm), width: 47 7/8 in. (121.6 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Nicolas Poussin, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album.

- 15. “Delivery of the Keys,” fresco painting by Pietro Perugino, c. 1481–1482

“This Pietro Perugino fresco is from the cycle of the life of Christ. Likely in charge of the entire project of fresco decoration on the walls of the Sistine Chapel, Perugino retained for himself not only representations on the altar wall (which eventually were replaced by Michelangelo’s ‘Last Judgment’) but also other significant scenes, such as this ‘Christ Handing the Keys to St Peter’ fresco (stylistically the most instructive), a most fitting subject for Pope Sixtus’ chapel. The main figures are organized in a frieze in two tightly compressed rows: The principal group, showing Christ handing the gold and silver keys to the kneeling St Peter, is surrounded by the other apostles, including Judas Iscariot (fifth figure to the left of Christ), all with halos. Scattered in the middle distance are two secondary scenes from the life of Christ, including the Tribute Money on the left and the Stoning of Christ on the right.”[1]

“In Matthew 16:13–20, we find a conversation between Jesus and his disciples regarding his identity. Jesus first asks them who people say he is; he then asks who the disciples say he is. Peter immediately and boldly declares that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God. In response, Jesus says that Peter’s declaration of faith will be the rock upon which the Lord will build his church. Jesus describes the authority that he’s delegated to them as the ‘keys to the kingdom of heaven.’ Peter and the rest of the apostles were assigned a crucial role in introducing the gospel to the world. In Christ’s name, they’ll declare that he is the Messiah and that faith in Jesus allows the only entrance into his heavenly kingdom. When the apostles declare something bound or loosed[2] in Jesus’ name, the power that resides in heaven will respond and make it so.”[3]

… Height: 10.8 ft. (330 cm), width: 18 ft. (550 cm) … Artistic details shown here by Khan Academy

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Pietro Perugino, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. -

• That ends “Christ Gives Peter the Keys to Heaven” . . .

• Now begins “The Transfiguration of Christ” Collection

16. “The Transfiguration of Christ,” tempera on panel, painted by Il Pordenone, 1518This “Transfiguration of Christ” panel by Il Pordenone (Giovanni Antonio de’ Sacchis) “shows an episode in the gospels where three apostles, for the first time, realize the divine nature of Jesus, who appears to them on a mountain, surrounded by brilliant light, accompanied by Moses and Elijah. The work was painted the same year as the Pala Pucci by Pontormo, 1518, and not surprisingly, Il Pordenone had made a trip in central Italy sometime earlier, so we can arguably see in this work the influence of Mannerism.”[1] This work is on display at Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, Italy.

“Recorded in Matthew, Mark, and Luke, Jesus takes Peter, James, and John with Him up to a ‘high mountain.’ Unnamed, today it’s what we call the Mount of Transfiguration because of what takes place next: ‘There he was transfigured before them. His face shone like the sun, and his clothes became as white as the light. Just then there appeared before them Moses and Elijah, talking with Jesus’ (Matt. 17:2–3). The transfiguration of Jesus on the mountain is significant, for it gave those three disciples a glimpse of the glory that Jesus had before the Incarnation and that He would have again.

“Years later, Peter refers to this event: ‘For we did not follow cleverly devised fables when we made known to you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but we were eyewitnesses of His majesty. For He received honor and glory from God the Father when the voice from the Majestic Glory came to Him, saying, ‘This is My beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.’ And we ourselves heard this voice from heaven when we were with Him on the holy mountain’ (2 Pet. 1:16–18).”[2]

Those three disciples never forgot what happened that day on that holy mountain; no doubt this was intended. John wrote in his gospel, “We have seen His glory, the glory of the one and only” (John 1:14), asserting that Jesus was truly, fully, physically human. Those who witnessed the transfiguration bore witness to it to the other disciples, as well as to countless millions down through the centuries.

… Height: 36.6 in. (93 cm), width: 25.1 in. (64 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Il Pordenone, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 17. “The Transfiguration of Christ,” oil on canvas, painted by Raphael, 1518–1520

Raphael (1483–1520) The Transfiguration (at Pinacoteca Apostolica) was the artist’s last painting. “Its composition is divided into two distinct parts: the Miracle of the Possessed Boy on a lower level; the Transfiguration of Christ on a mount in the background. The transfigured Christ floats in an aura of light and clouds above a hill, accompanied by Moses and Elijah. Below, on the ground, are Christ’s disciples; some are dazzled by the light of glory, others are in prayer. The gestures of the crowd beholding the miracle link both parts together: the raised hands of the crowd converge toward the figure of Christ.”[1]

“Recorded in Matthew, Mark, and Luke, Jesus takes Peter, James, and John with Him up an unnamed ‘high mountain.’ Today it’s what we call the Mount of Transfiguration because of what took place: ‘There he was transfigured before them. His face shone like the sun, his clothes became as white as light. Just then there appeared before them Moses and Elijah, talking with Jesus’ (Matt. 17:2–3). Watch this excellent, informative narrated video highlighting Raphael’s Transfiguration masterpiece.

“The transfiguration of Jesus on the mountain is significant, for it gave those three disciples a glimpse of the glory that Jesus had before the Incarnation and that He would have again. While praying, Jesus’ personal appearance was changed into a glorified form and His clothing became dazzling white. Moses and Elijah appeared and talked with Jesus about His death that would soon take place. Peter, not knowing what he was saying and being very fearful, offered to put up three shelters for them. The disciples never forgot what happened that day on the mountain and no doubt this was intended.”[2]

… Height: 13.3 ft. (405 cm), width: 9.1 ft. (278 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Raphael, via Wikimedia Commons: CC BY-SA 4.0

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 18. “The Transfiguration of Christ,” opaque watercolor on wove paper, painted by James Tissot, 1886–1896

[ James Tissot (French, 1836–1902): “The Transfiguration (La transfiguration),” 1886–1896. Brooklyn Museum, purchased by public subscription, 00.159.145 (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 00.159.145_PS1.jpg); see Tissot’s “Life of Christ” collection of 124 watercolors selected from a set of 350 that depict detailed New Testament scenes.]

In the passage illustrated here, “Jesus again retreats to a mountaintop with his disciples, Peter, James, and John, to pray. He is transformed before the eyes of his companions in the course of his prayers; his robes emit a blinding white light. Prophets Elijah and Moses suddenly appear to converse with him. In Tissot’s rendering, one apostle shields his eyes from the brilliant glow while another covers his ears as God’s supernatural voice declares Jesus his beloved Son.”[1]

“About a week after Jesus plainly told His disciples that He would suffer, be killed, and be raised to life (Luke 9:22), He took Peter, James, and John up a mountain to pray. While praying, His personal appearance was changed into a glorified form; His clothing became dazzling white. Moses and Elijah appeared and talked with Jesus about His death that would soon take place. Undoubtedly, the purpose of Christ’s transfiguration into at least a part of His heavenly glory was so that the ‘inner circle’ of His disciples could gain a greater understanding of who Jesus was. Christ underwent a dramatic change in appearance in order that the disciples could behold Him in His glory. The disciples, who’d only known Him in His human body, now had a greater realization of the deity of Christ, though they couldn’t fully comprehend it. That gave them the reassurance they needed after hearing the shocking news of His upcoming death.”[2]

… Height: 9 1/2 in. (24.1 cm), width: 6 1/16 in. (15.4 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Brooklyn Museum

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album.

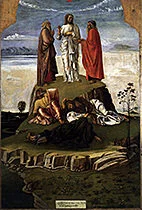

- 19. “Transfiguration of Christ,” tempera on panel, painted by Giovanni Bellini, 1454–1460

This “Transfiguration of Christ” is a Giovanni Bellini painting, now in the Museo Correr in Venice.[1] He created two Transfiguration masterpieces, the other one is housed in the Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy [see slide 22]. “Jesus is dressed in a white, now slightly gray robe, which is splendidly drawn in almost translucent colors. Moses and Elijah, standing near Jesus, are painted as patriarchs with long white beards and flowing white hair, both dressed in light-red cloaks. The gray-haired apostle, Peter, sits on the left. Most important is his focus on Jesus being the godly redeemer.”[2]

“Recorded in the synoptic gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, Jesus takes Peter, James, and John with Him up to an unnamed mount. ‘There he was transfigured before them. His face shone like the sun, and his clothes became as white as the light. Just then there appeared before them Moses and Elijah, talking with Jesus’ (Matt. 17:2–3). The transfiguration of Jesus on the mountain is significant, for it gave those three disciples a glimpse of the glory that Jesus had before the Incarnation and that He would have again. While praying, Jesus‘ personal appearance was changed into a glorified form, and His clothing became dazzling white. Moses and Elijah appeared and talked with Jesus about His death that would soon take place. Peter, not knowing what he was saying and being very fearful, offered to put up three shelters for them. The disciples never forgot what happened that day on the mountain and no doubt this was intended.”[3]

… Height: 61 in. (154 cm), width: 46 in. (116 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Giovanni Bellini, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 20. “The Transfiguration of Christ,” oil on canvas by Peter Paul Rubens, 1605

Similar to Raphael’s “The Transfiguration of Christ” [see slide 17], this large oil painting composition of the same name by Peter Paul Rubens is also “divided into two distinct parts: the Miracle of the Possessed Boy on a lower level and the Transfiguration of Christ on a mount in the background. And similarly, the transfigured Christ floats in an aura of light and clouds above the hill, accompanied by Moses and Elijah. Below them, on the ground, are Christ’s disciples; some are dazzled by the light of glory, others are in prayer. The gestures of the crowd below, beholding the miracle, effectively link the two parts together; the raised heads and hands of the crowd converge toward the figure of Christ.”[1]

“It was about a week after Jesus plainly told His disciples that He’d suffer, be killed, and be raised to life (Luke 9:22), that he took Peter, James, and John up a mountain to pray. While praying, His personal appearance was changed into a glorified form; His clothing became dazzling white. Moses and Elijah appeared and talked with Jesus about His upcoming death. Undoubtedly, the purpose of the transfiguration of Christ into at least a part of His heavenly glory was so that the ‘inner circle’ of His disciples could gain a greater understanding of who Jesus was. Christ underwent a dramatic change in appearance in order that the disciples could behold Him in His glory. The disciples, who had only known Him in His human body, now had a greater realization of the deity of Christ, though they could not fully comprehend it. That gave them the reassurance they needed after hearing the shocking news of His coming death.”[2]

… Height: 13.3 ft. (407 cm), width: 21.9 ft. (670 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Peter Paul Rubens, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

… See eight additional Rubens’ oil paintings in our “Peter Masterpieces” albums: Album 4 (5@); 5; 9; and 16.

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 21. “Transfiguration,” oil on panel, painted by Giovanni Savoldo, 1530

According to Wikipedia, this “c.1530, oil-on-panel ‘Transfiguration’ painting is by Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo. From the gospel episode of Jesus’ transfiguration, it’s now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy”[1]

“About a week after Jesus plainly told His disciples that He would suffer, be killed, and be raised to life (Luke 9:22), He took Peter, James, and John up a mountain to pray. While praying, His personal appearance was changed into a glorified form, and His clothing became dazzling white. Moses and Elijah appeared and talked with Jesus about His death that would soon take place.

“Christ underwent a dramatic change in appearance in order that the disciples could behold Him in His glory. The disciples who had only known Him in His human body now had a greater realization of the deity of Christ, though they could not fully comprehend it. That gave them the reassurance they needed after hearing the shocking news of His coming death. Christ underwent a dramatic change in appearance in order that the disciples could behold Him in His glory. The disciples, who had only known Him in His human body, now had a greater realization of the deity of Christ, though they could not fully comprehend it. That gave them the reassurance they needed after hearing the shocking news of His coming death. The disciples never forgot what happened that day on the mountain and no doubt this was intended.”[2]

… Height: 54.7 in. (139 cm), width: 49.6 in. (126 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Girolamo Savoldo, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 22. “Transfiguration of Christ,” oil on wood panel, painted by Giovanni Bellini, c. 1487

The Transfiguration of Christ “This is the second and final version of Giovanni Bellini’s subject painting, differing from the earlier rendering; his first was executed c. 1455 [shown here]. Herein the event is no longer supernatural and the mount is reduced to a slight rise. At the left a farmer leads an ox and goat past a monastery on a crag that is already darkening in the evening shadows; Christ stands in the center of this chilly landscape, his hands and head silhouetted against the shining white clouds; the flanking figures of Moses and Elijah have all the majesty of the Old Testament. Beneath this group the three apostles have fallen to the ground. A rocky chasm creates an explicit separation between the observer and the holy event.”[1]

Jesus stands between renowned Old Testament prophets, Elijah (right) and Moses. Christ’s face looks to the clouds on the horizon while his hands are wide open. Unlike Bellini’s first version, here Jesus doesn’t look like he’s engaging Elijah and Moses verbally. The faces of Moses and Elijah bow to Christ, symbolizing his supremacy. As opposed to biblical text, Bellini doesn’t represent this event to be supernatural: While Christ’s clothing is bright, it doesn’t glow, a sign of paranormal phenomena. The three disciples — Peter, James, and John — look astonished by the event unfolding before them. This Bellini episode fails to show the supernatural nature of Christ’s transfiguration in that Jesus, Elijah, and Moses aren’t glowing. The sky looks normal for an evening and people are going about their routine. Three gospel accounts accurately describe Jesus’ transfiguration: Matthew 17:1–8; Mark 9:2–8; Luke 9:28–36.

… Height: 45.2 in. (115 cm), width: 59.8 in. (152 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, and image enlargement: public domain, via Web Gallery of Art; Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 23. “The Transfiguration,” egg tempera on wood, painted by Duccio di Buoninsegna, 1308–1311

Duccio di Buoninsegna was “an Italian painter active in Siena, Tuscany, in the late 13th and early 14th century. He was hired throughout his life to complete many important works in government and religious buildings around Italy.”[1]

“Christ stands at the center of a small square panel amid the Maestà (Majesty) Predella Panels. [To see many more of Duccio’s Maestà creations that feature Peter, open Warren Camp’s Albums #2, 4, 8, 9, 13, 14, and 15.] The moment shows the Transfiguration, when Jesus ascended a mountain and became filled with heavenly light, shown here by the golden stripes on his robes. Suddenly the Old Testament prophets, Moses (on his left) and Elijah (on his right), appeared and began to speak with him. God then spoke, singling out Christ as divinely favored: ‘This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased. Listen to him!’ (Matthew 17:5b NIV)

“The disciples Peter, James, and John are kneeling below; they raise their hands up to shield their faces and recoil in fear. The Transfiguration prefigured the Resurrection and Ascension, when Christ ascended in glory from this earth.”[2]

The purpose of Christ’s transfiguration into at least a part of his heavenly glory was to enable his “inner circle” of disciples to gain a greater understanding and appreciation of who Jesus was. See the full account of Jesus’ transfiguration in all three gospels: Matt. 17:1–8; Mark 9:2–8; Luke 9:28–36.

… Height: 19 in. (48.5 cm), width: 20 1/4 in. (51.4 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: The National Gallery, London; presented by R.H. Wilson, 1891

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. -

• That ends “The Transfiguration of Christ” . . .

• Now begins “Tribute Money #1: The Temple Tax”

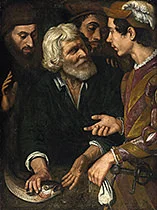

24. “Miracle of St Peter and the Fish,” oil on canvas, the Italian School, 1700sThe “Miracle of St Peter and the Fish” This “17th-century painting in Italy was an international endeavor. Large numbers of artists traveled to Rome, especially, to work and study. They sought not only the many commissions being extended by the Church but also the chance to learn from past masters. Most of the century was dominated by the baroque style.”[1] Although it isn’t documented from which Italian school this artist trained, he likely came from one or more of these Italian schools: the Roman, Bolognese, Tuscany, Venetian, Ferrarese, Florentine, Sienese, Lucchese, or Pisan School.

What is the temple tax? “This tax was required of Jewish males over age 20, and the money was used for the upkeep and maintenance of the temple. In Exodus 30:13–16, God told Moses to collect this tax at the time of the census taken in the wilderness. In 2 Kings 12:5–17 and Nehemiah 10:32–33, it seems the temple tax was paid annually, not just during a census. This two-drachma tax wasn’t a large sum of money, but roughly equivalent to two days’ wages.

“The temple tax is also mentioned in the New Testament in Matthew 17:24–27 when Peter was confronted by the religious leaders collecting the tax. They asked Peter, ‘Doesn’t your teacher pay the temple tax?’ (v. 24). The leaders may have been attempting to prove Jesus’ disloyalty to the temple or His violation of the Law. Peter affirmed that Jesus did pay the temple tax. When Peter came into the house where Jesus was, the Lord asked him, ‘From whom do the kings of the earth collect duty and taxes — from their own children or from others?’ Peter replied that kings collect from others because their children are exempt. Jesus’ point was that, since the temple was His Father’s house, Jesus was exempt. Why should the Son of God pay a tax to His own Father?

“Although Jesus, as the Son of God, and His disciples were exempt from paying the temple tax, they would pay the tax in order to not offend Jewish leaders. Jesus then instructs Peter to throw out a fishing line, which would result in a catch. When Peter opened the fish’s mouth, he found a coin that happened to be the correct amount for the temple tax for him and Jesus… Jesus used the question about the temple tax to teach a lesson: Christians are free, but they must sometimes relinquish their rights in order to uphold their witness and not cause others to stumble. True freedom is not serving ourselves but others.[2]

… Height: 41 3/4 in. (106 cm), width: 31 3/4 in. (80.6 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Italian School, 17th century, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 25. “Saint Peter Finding the Tribute Money,” oil on canvas, painted by Peter Paul Rubens, 1617–1618

Peter Paul Rubens “was the most gifted, versatile, and influential of all seventeenth-century Flemish artists. He was a painter to various courts of Europe, producing magnificent cycles of allegorical paintings glorifying his princely patrons. He also served as a diplomat.

“The gospel of Matthew [read 17:24–27, titled ‘The Temple tax’] describes how Peter was asked in Capernaum whether his teacher paid the temple tax. In response, Christ told Peter to go to Lake Kinneret, take out the first fish he caught, and open its mouth. There in its jaws he would find the money to pay the temple tax. The subject was relatively rare in seventeenth-century European art and may have been commissioned by a fishermen’s guild.”[1]

This painting is one of many in Warren Camp’s photo album collection that depicts the first of two “Tribute Money” accounts found in the New Testament; it highlights “The Temple Tax” described in Matthew’s gospel, which has Peter finding in a freshly caught fish’s mouth a coin that would sufficiently pay the temple tax for him and Lord Jesus, the Son of God. The second “Tribute Money” account, also found in Matthew’s gospel, illustrates “Tribute Paid to Caesar.” Matt. 22:15–22 reveals how the Pharisees and Herodians conspired to trap Jesus. However, he avoided their trap altogether by saying, “Show me the coin used for paying the tax.” Jesus followed up with one of his most often quoted statements, “So give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s.” [Camp’s photo album contains five “Temple Tax” painted masterpieces followed by five “Tribute Money Paid to Caesar” artworks.]

… Height: 78.5 in. (199.4 cm), width: 86.1 in. (218.8 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Peter Paul Rubens, CC0 1.0, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

… See eight additional Rubens’ oil paintings in our “Peter Masterpieces” albums: Album 4 (5@); 5; 9; and 16.

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 26. “Tribute Money,” oil on canvas, painted by Mattia Preti, c. 1640

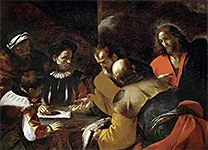

The theme treated here in Preti’s “Tribute Money” is the biblical tale involving a question that Jewish tax collectors had asked Peter: “Doesn’t your teacher pay the temple tax?” Jesus then asked Peter, “What do you think, Simon?” (Matthew17:24–25 NIV). “In the dark brown tones of the painting, we can barely make out the six figures half illuminated by a light from some indiscernible source. The tax collector pauses in his writing as Peter hands him a coin, indicating the miracle that has just occurred: Peter found the coin in a fish he had caught at the command of Christ (v. 27).”[1]

In Matthew 17:24–27, Jesus used three questions about the temple tax to teach a lesson. Ruled by Rome, the Jewish people had to pay the temple tax, an annual two-drachma payment that supported the Jerusalem temple. This tax wasn’t a large sum of money; it was roughly equivalent to two days’ wages, collected from every Jew, twenty years and older. Jesus — and the believers — as the king’s (God’s) sons/subjects, would have been exempt in principle from paying that tax. Jesus’ point was that, since the temple was his Father’s house, Jesus — God’s son — was exempt. After all: Why should the Son of God pay a tax to his Father? Although he didn’t owe a temple tax, Jesus made Peter understand that Christians should shoulder their duties as ordinary citizens, even when they’re unpleasant.

… Height: 75.9 in. (193 cm), width: 56.2 in. (143 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Mattia Preti, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 27. “Peter Paying the Temple Tax,” pen and black ink on wove paper, drawn by Gustav Heinrich Naeke, 1820–1821

Gustav Naeke’s pen-and-ink drawing titled “Peter Paying the Temple Tax,” presents Peter in its center, paying the tax collector the customary two-drachma temple tax. But we see Peter again in the far-left distance; kneeling at a shore, his head haloed while holding a fish in his hands. It’s there that he retrieves a shekel coin (the equivalent of four Roman drachmas) from a fish’s mouth before paying the tax collector the temple tax. In Matthew 17:24, Jesus paid the tax for himself and Peter, using that one shekel coin!

What is the temple tax? This tax was required of Jewish males over age 20. The money was used for temple maintenance and upkeep. Ruled by Rome, the Jewish people had to pay a temple tax — an annual two-drachma payment that was used to help service Jerusalem’s temple. This tax wasn’t a large sum of money; it was roughly equivalent to two days’ wages. Jesus — and the believers — as the king’s (God’s) sons/subjects would have been exempt in principle from paying that tax. Jesus’ point was that, since the temple was his Father’s house, Jesus — albeit God’s son — was exempt. After all: Why should the Son of God pay a tax to his Father? Although he didn’t owe a temple tax,[1] Jesus made Peter understand that Christians should shoulder their duties as ordinary citizens, even when it’s unpleasant to do so.

… Height: 9 15/16 in. (25.2 cm), width: 7 3/4 in. (19.7 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: National Gallery of Art; Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 28. “The Tribute Money,” painted fresco by Masaccio, c. 1426

“Tribute Money” This episode depicts “the arrival in Capernaum of Jesus and the apostles, based on Matthew 17:24–27. Masaccio has included three different moments of this story in the same scene: (1) illustrated in the center is the tax collector’s request, with Jesus’ immediate response indicating to Peter how to find the requisite money; (2) Peter catching a fish in the Sea of Galilee and extracting the coin is shown to the left; and, (3) to the right, Peter hands the temple tax tribute money to the tax collector. [Peter paid the tax for himself and Jesus, using the shekel coin retrieved from a fish’s mouth.]”[1]

The temple tax was required of Jewish males over age 20. The money was used for temple maintenance and upkeep. Ruled by Rome, the Jewish people had to pay a temple tax — an annual two-drachma payment that was used to help service Jerusalem’s temple. This tax wasn’t a large sum of money; it was roughly equivalent to two days’ wages. Jesus and the believers, as the king’s (God’s) sons/subjects, would have been exempt in principle from paying that tax. Jesus’ point was that, since the temple was his Father’s house, Jesus (God’s son ) was exempt. Why should the Son of God pay a tax to his Father? Although he didn’t owe a “temple tax,”[2] Jesus made Peter understand that Christians should shoulder their duties as ordinary citizens, even when it’s unpleasant to do so.

Masaccio’s “Tribute Money” is particularly remarkable for its early use of both linear and atmospheric perspective to integrate figures, architecture, and landscape into a consistent whole. Watch this descriptive video that highlights Masaccio’s intent, styles, and techniques used in this creation.

… Height: 8.5 ft. (260 cm), width: 19 3/4 in. (599 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Masaccio, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

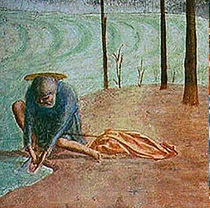

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 29. Detail #1 of Masaccio’s “Tribute Money” Fresco

A story unfolds and a miracle is performed…

In this fresco, Masaccio presents Christ and Peter being confronted by a Roman tax collector to pay the two-drachma temple tax, despite their having no money available. Christ points to the left where we find another depiction of Peter, this time he’s performing a miracle. Here in detail #1, look closely. You can see a haloed, kneeling Peter removing a coin from the mouth of a fish that he’d just caught.

Tribute Money is one of many frescoes painted by Masaccio (along with another artist named Masolino) in the Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, in Florence, Italy. All of the frescoes in the chapel recount events in Peter’s life. This “Tribute Money” account is told in three separate scenes embodied within one fresco. The technique of telling multiple aspects of a story within the same painting is called “continuous narrative.”

Here’s the breakdown of Masaccio’ three-part continuous narrative: In the center of the fresco [detail # 2, see slide 30], you’ll see the tax collector demanding money from Christ and Peter. Christ then directs Peter to perform a specific task, which Masaccio depicts in the far-left portion of his fresco [detail #1, above]: Peter kneels down and miraculously extracts a shekel coin from a fish’s mouth. On the far right [detail # 3, see slide 31], Peter intentionally pays the tax collector the temple tax on behalf of Christ and himself. [Learn more about the temple tax here.]

This story is found only in the gospel of Matthew (17:24–27). He himself was a tax collector, according to his own admission (Matt. 9:9–13).

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 30. Detail #2 of Masaccio’s “Tribute Money” Fresco

A story unfolds and a miracle is performed…

In this narrative fresco, Masaccio presents Christ and Peter, both pointing to the left-hand portion of this three-part painting. Here in detail #2, we see a Roman tax collector (without a halo, wearing orange) ordering Christ, Peter, and other apostles to pay the temple tax. But no one has money with them.

Christ, in the center, instructs Peter to do as follows: “But so that we may not cause offense, go to the lake and throw out your line. Take the first fish you catch; open its mouth and you will find a four-drachma coin. Take it and give it to them for my tax and yours” (Matthew 17:27). Christ Jesus indeed performed a miracle: In a fish’s mouth he provided the required amount of money — one shekel — to pay to the tax collector the temple tax — a half-shekel per man — on behalf of Jesus and Peter.

Here’s the breakdown of Masaccio’ three-part continuous “Tribute Money” narrative: In the center of the fresco [detail # 2, above], you’ll see the tax collector demanding money from Christ and Peter. Christ then directs Peter to perform a specific task, which Masaccio depicts in the far-left portion of his fresco [detail #1, see slide 29]: Peter kneels down and miraculously extracts money from a fish’s mouth. On the far right [detail # 3, slide 31], Peter intentionally pays the tax collector the temple tax on behalf of Christ and himself. [Learn more about the temple tax here.]

This story is found only in the gospel of Matt. (17:24–27). He himself was a tax collector, according to his own admission (Matt. 9:9–13).

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 31. Detail #3 of Masaccio’s “Tribute Money” Fresco

A story unfolds and a miracle is performed…

Detail #3 of Masaccio’s “Tribute Money” highlights the final scene of this biblical narrative, shown in the right-hand portion of this continuous narrative fresco: Peter intentionally pays the tax collector the temple tax.

The four-drachma coin (equivalent to a shekel) that Peter had pulled from the freshly caught fish [shown in detail #1, slide 29] was the prescribed amount of tax payment for two people, which in this story was Jesus and Peter. Matthew recounts this in his gospel: “But so that we may not cause offense, go to the lake and throw out your line. Take the first fish you catch; open its mouth and you will find a four-drachma coin. Take it and give it to them for my tax and yours” (Matt. 17:27).

Here’s the breakdown of Masaccio’ three-part continuous narrative: In the center of the fresco [detail # 2, see slide 30], you’ll see the tax collector demanding money from Christ and Peter. Christ then directs Peter to perform a specific task, which Masaccio depicts in the far-left portion of his fresco [detail #1, see slide 29]: Peter kneels down and miraculously extracts money from the mouth of a fish. On the far right [detail # 3, shown above], Peter pays the tax collector the temple tax on behalf of Christ and himself. [Learn more about the temple tax here.]

This story is found only in the gospel of Matthew (17:24–27). He himself was a tax collector, according to his own admission (Matt. 9:9–13).

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. -

• That ends “Tribute Money #1: The Temple Tax” . . .

• Now begins “Tribute Money #2: Payment to Caesar”

32. “The Tribute Money (Le denier de César),” watercolor on paper, painted by James Tissot 1886–1894[ James Tissot (French, 1836–1902): “The Tribute Money (Le denier de César),” 1886–1894. Opaque watercolor over graphite on gray wove paper. Brooklyn Museum, purchased by public subscription, 00.159.206 (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 00.159.206_PS1.jpg); see Tissot’s “Life of Christ” collection of 124 watercolors selected from a set of 350 that depict detailed New Testament scenes.]

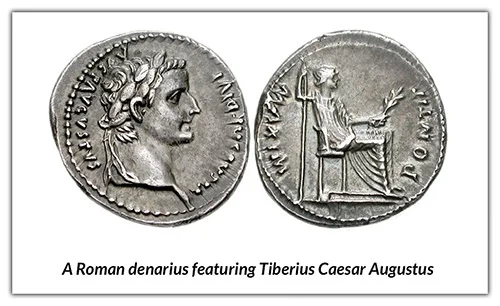

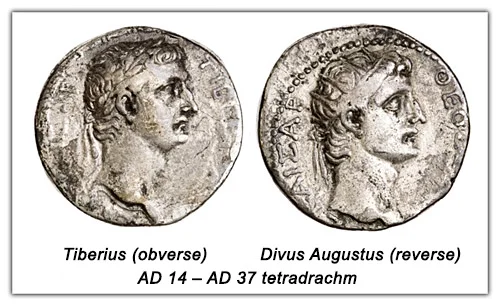

“Jesus is being watched carefully by the priests and scribes who hope to have him arrested as a threat to Roman rule. Asked whether tribute should be paid to Rome, Jesus points to a coin inscribed with the likeness of the emperor and raises another hand to the sky, saying, ‘Render therefore unto Caesar the things which be Caesar’s, and unto God the things which be God’s (Matthew 22:21).” Distinguishing between terrestrial and divine authority, Jesus evades the trap as his hostile audience crowds around him, intently listening to his response.”[1] … See this photo of the coin presumed to be mentioned in all three synoptic gospels.

What did Jesus mean when He said, “Render to Caesar what is Caesar’s”? … This was “a well-known quote that is part of Jesus’ response to a joint attempt by the Herodians and Pharisees to make Jesus stumble in front of His own people. In Matt. 22, Jesus had just returned to Jerusalem. His enemies saw an opportunity to put Him on the spot in front of His followers. In v. 17, they say to Jesus, ‘Tell us then, what is your opinion? Is it right to pay the imperial tax to Caesar or not?’ It was a trick question. If Jesus answered, ‘No,’ the Herodians would charge Him with treason against Rome. If He said, ‘Yes,’ the Pharisees would accuse Him of disloyalty to the Jewish nation and He’d lose the support of the crowds. To pay taxes or not to pay taxes? The question was designed as a Catch-22.

“Jesus’ response is nothing short of brilliant. After He asked the crowd, ‘Show me the coin for the tax,’ they brought him a denarius, a coin used as the tax money at the time. With the coin displayed in front of them, Jesus said, ‘Whose likeness and inscription is this?’ The Herodians and Pharisees, stating the obvious, said, ‘Caesar’s.’ Then Jesus brought an end to their foolish tricks: ‘Therefore render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s’ (v. 21 ESV).”[2]

… Height: 7 5/8 in. (19.4 cm), width: 10 7/16 in. (26.5 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Brooklyn Museum

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album.

- 33. “The Tribute Money,” etching on laid paper by Rembrandt van Rijn, c. 1635

Rembrandt was a 17th-century painter and etcher whose work came to dominate what’s since been named the Dutch Golden Age. He’s considered as one of the greatest painters and printmakers in European art and the most important in Dutch history.

“In this New Testament episode (Matthew 22:15–22), men come to ask Jesus whether or not Jews should pay taxes levied on them by Romans under Caesar. In response to this attempt to trick him he states, ‘Render therefore unto Caesar the things which be Caesar’s, and unto God the things which be God’s (Matt. 22:21) Religious scholars have understood this phrase to call for a separation of church and state and to champion complete devotion to God. Whatever the interpretation, the image stands alone as a work of art of intimate dimensions. Rembrandt conveyed the tension of the moment through a densely layered composition. He has set the grace and poise displayed on Christ’s features against expressions of concentration, skepticism, and even frustration on the faces around him.”[1]

What did Jesus mean when He said, “Render to Caesar what is Caesar’s”? … “He was drawing a sharp distinction between two kingdoms. There is a kingdom of this world, and Caesar holds power over it. But there is another kingdom, not of this world, and Jesus is King of that kingdom (John 18:36). Christians are part of both kingdoms, at least temporarily. Under Caesar, we have certain obligations that involve material things. Under Christ, we have other obligations involving things eternal. If Caesar demands money, give it to him — it’s only mammon. But make sure you also give God what He demands.”[2]

… Height: 3 1/16 in. (7.8 cm), width: 4 3/16 in. (10.7 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: National Gallery of Art; Rosenwald Collection

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 34. “The Tribute Money,’ oil on canvas, painted by Bernardo Strozzi, 1630s

Bernardo Strozzi, “The Tribute Money” “Jesus replied to the Pharisees, ‘Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.’ They wanted to trick him into a subversive answer and asked him: ‘Is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar, or not?’ (Matthew 22:21 and 17) In this lively composition painted after 1631, Strozzi contrasts Christ’s humble wisdom to the malicious curiosity of his opponents ready to retort. The Pharisee holding the coin seems to step into the picture from the viewer’s space, and the role of the little boy looking out is also to involve the viewer.”[1] … See this photo of the coin presumed to be mentioned in all three synoptic gospels.

What did Jesus mean when He said, “Render to Caesar what is Caesar’s”? … “He was drawing a sharp distinction between two kingdoms. There is a kingdom of this world, and Caesar holds power over it. But there is another kingdom, not of this world, and Jesus is King of that kingdom (John 18:36). Christians are part of both kingdoms, at least temporarily. Under Caesar, we have certain obligations that involve material things. Under Christ, we have other obligations that involve things eternal. If Caesar demands money, give it to him — it’s only mammon. But make sure you also give God what He demands.”[2]

You can read the biblical account of “Paying the Imperial Tax to Caesar” in all three synoptic gospels: Matt. 22:15–22; Mark 12:13–17; and Luke 20:20–26.

… Height: 5.18 ft. (1580 mm), width: 7.38 ft. (2250 mm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Bernardo Strozzi, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

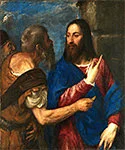

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 35. “The Tribute Money,” oil on poplar panel, painted by Titian, c. 1516

The Tribute Money is a 1516 oil-on-panel painting by the Italian late-Renaissance artist Titian. It depicts a Pharisee presenting a coin to Christ who responds saying, “Render to Caesar what is Caesar’s.” It’s signed “Ticianus F.” [for Ticianus fecit, meaning “made by Titian”] on the trim of the Pharisee’s collar [the shadowed left side]. “It’s also Titian’s earliest signed painting. Much later, Titian painted a larger composition of this subject [see next slide].”[1]

“The evangelist Matthew reports how the Pharisees tried to set a trap for Christ. When asked whether it was right to pay taxes to the emperor in Rome, Jesus was shown a coin. He pointed to the portrait of the ruler and answered: ‘So give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s’ (Matt. 22:21 NIV). With this replica, Christ had cleverly avoided making himself vulnerable as a unilateral party leader to either the Jewish population or the Roman occupying power. Titian bundles the whole story in a single contrast: On the left, the beautiful figure of the Son of God; on the right the overgrown figure of the Pharisee. In the serene twist with which Christ turns to the Pharisee, Jesus’ sovereignty is meaningfully expressed. Titian created this early work for the Duke of Ferrara, Alfonso I d’Este. Probably this wooden panel was intended for the door of a cabinet in which the duke kept his famous coin and medal collection.”[2]

What did Jesus mean when he said, “Render to Caesar what is Caesar’s”? Read the biblical accounts of “Paying the Imperial Tax to Caesar”: Matt. 22:15–22; Mark 12:13–17; and Luke 20:20–26… See this photo of the coin presumed to be mentioned in the text of all three synoptic gospels.

… Height: 29.5 in. (75 cm), width: 22 in. (56 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: Titian, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

… The artist’s short biography; his other works of art

Return to “Peter Masterpieces” album’s opening page or to the top of this page or open the next album. - 36. “The Tribute Money,” oil on canvas, painted by Titian, c. 1560

This more-recent oil-on-canvas painting of Titian’s “The Tribute Money” depicts the account presented in all three synoptic gospels in which the Pharisees (chief priests) and scribes were opponents of Christ. They asked him whether it was right to pay tax to the Romans who ruled Palestine. Christ, realizing their attempt to trap him, asked them whose likeness and name were on the coin: “Caesar’s,” they replied. Then he said to them, “So give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s” (Matthew 22:21). “Titian has painted the Pharisee in the foreground, offering the golden coin to Christ, and a scribe wearing spectacles behind him. This subject is rare in art. Titian may have been the first artist to represent it in his famous painting of 1516 [see previous slide]”[1]

“Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574; Italian painter, architect, engineer, writer, and historian) thought that Titian’s head of Christ was ‘stupendous and miraculous,’ while all artists at the time believed it to be Titian’s most perfect painting. Much earlier, Titian painted a smaller composition of this subject [see previous slide].”[2] He signed both paintings with the usual “Ticianus F.” [for Ticianus fecit, meaning “made by Titian”]; you can see his uppercase signature on the stone wall behind Christ’ shoulder… See this photo of the coin that’s presumed to be mentioned in the text of all three synoptic gospels.

What did Jesus mean when he said, “Render to Caesar what is Caesar’s”? … The biblical explanation is here while Wikipedia’s is here.

You can read the biblical account of “Paying the Imperial Tax to Caesar” in all three synoptic gospels: Matt. 22:15–22; Mark 12:13–17; and Luke 20:20–26.

… Height: 44.1 in. (112.2 cm), width: 40.6 in. (103.2 cm)

… Photo source, license, attribution, museum details, and image enlargement: The National Gallery