2 Samuel 5:1–10 . . . Bible Study Summary with Videos and Questions

“David Becomes King over Israel”

In the first five verses of 2 Samuel 5, we’ll see David, at long last, be anointed king of all Israel. It started many years before, when he must have been in his teens. Much to his and his family’s surprise, he was initially anointed as the next king of Israel. It was approximately 15 years prior to his being anointed king of Judah, and another seven prior to the elders of Israel anointing him king of all Israel. After three anointings, the author highlights a kingship covenant that he made in Hebron to become Israel’s next king.

Before we explore the essentials of the first half of chapter 5, it’s important to appreciate these seven lessons related to the long delay in David finally becoming king: (1) We should begin by observing that God’s promise to Israel and David (implied when Samuel first anointed him) took a long time being fulfilled; (2) the delay in his becoming Israel’s king wasn’t unusual, but was typical of the way God brings about his promises and purposes — God wasn’t in a hurry; (3) it’s while waiting for God that many fail in their faith and obedience; (4) Satan often attacks by trying to capitalize on delays; (5) times of waiting on the Lord often occur when our faith is stretched and our intimacy with him is enhanced; (6) waiting isn’t necessarily a time of passivity, but is a significant part of each of our lives; and finally, (7) be assured that God always makes waiting worthwhile.

May we learn well from David that waiting is a part of the normal Christian life. We’ll be tempted to shortcut our waiting, but that could cause problems. So let’s resolve in our hearts to be like David, waiting upon the Lord to fulfill his purposes and promises, in his good time. Rest assured that, while we wait, God’s working in us to prepare us for the good things that lie ahead. Never doubt that we’ll see them. While we wait, let’s devote ourselves to doing the good that we’re able to do and know to do.

[Note: Click the link to This Week’s Passage near the bottom of this page to read today’s Scripture.]

Israel Accepts David as “God’s King” (2 Samuel 5:1–5)

The fact that Samuel had first anointed a youthful David was then common knowledge in Israel. Therefore we might regard previous efforts of resistance to his assuming the throne after Saul’s death as actively resisting the known will of God. The covenant (v. 3) was an agreement in front of God, between the people and the king. It probably included a fresh commitment to the Mosaic Covenant. And, it might have taken some time for this covenant to be realized, since a variety of tribal elders had to decide what to do in the absence of a king from Saul’s house. But finally they agreed and gathered at Hebron.

Here in chapter 5, David becomes king of all Israel while, at the same time, and finally obtains a place of his own: the city of Jerusalem. Up until now, that place has been called Jebus. Its inhabitants were called Jebusites. After conquering Jerusalem from the Jebusites, David made the fortress his residence, naming it the "City of David." As we’ll soon see, King Hiram of Tyre, sent messengers to David with cedar trees, carpenters, and masons, and they built David a house — meaning a royal palace in Jerusalem, which marked the establishment of his permanent home and seat of government as king over the united tribes of Israel.

5 1All the tribes of Israel came to David at Hebron and said, “We are your own flesh and blood. 2In the past, while Saul was king over us, you were the one who led Israel on their military campaigns. And the Lord said to you, ‘You will shepherd my people Israel, and you will become their ruler.’”

3When all the elders of Israel had come to King David at Hebron, the king made a covenant with them at Hebron before the Lord, and they anointed David king over Israel (2 Sam. 5:1–3).

The elders of Israel spoke what they’d concluded in their tribal councils, that David should be king because of: (1) Identity — David was one of them, a true Israelite; (2) Military prowess — David had led Saul’s troops against the Philistines; and (3) God’s approval — God had spoken prophetically that David should be their king. We don’t have a record of such prophecy, but, before he died, Samuel might have spoken publicly about what God had shown him. So a covenant (Hebrew: berît) was made between the king and his people.

The author puts the Israelites in the spotlight in vv. 1–3. It was they who came to David in Hebron and recognized and anointed him as their king. Remember: It was the people who initiated the push for a worldly king (with a lowercase “k”); the people sought Saul to become their king. We won’t be able to grasp the significance of the Israelites submitting to David to become God’s king without comparing and contrasting this event with what had been undertaken in 1 Samuel 8:1–22, where the Israelite people demanded that Saul be given to them as their first king. [Read the details of that outright demand in Week 7’s summary titled “Give Us a King to Lead Us!”] The elders of Israel came to aging Samuel, demanding that he give them a king, “to judge them, like all the nations” (8:5). They wanted a king to lead them in war and give them victory over their enemies.

Here in 2 Samuel 5, we see a distinct change, not just that change from a pathetic king such as Saul to a patriotic leader like David, but we ought to also see the change in the people. Realize at this point that there’s no crisis, no pressing danger to force the Israelite leaders to act. Saul was dead, along with his sons, including Ish-Bosheth. There’s was no Philistine attack, no Ammonite threat. In 1 Samuel 8, the Israelites rebelled against God as their King (capital “K”); here, their leaders acted out of obedience to God, not in rebellion against him. The king they gained in David was, in some measure, the king they deserved. When they approached David, they acknowledged several important truths that provided the basis for David’s kingship and their submission to him as their king.

It shouldn’t surprise us to see David being anointed as Israel’s king by these elders; it was done in the context of the covenant that David made before the Lord (v. 3), which was an act of obedience and faith. It was nothing like the confrontation between Samuel and Israel’s elders in 1 Samuel 8. David’s was a reign of righteousness, largely because of the repentance and obedience of the people of Israel and their leaders.

David Captures the City of Jebus (vv. 6–10)

In the Old Testament, Jebus was first described as one of the cities belonging to the sons of Judah, who were unable to eradicate the Jebusites from it (Joshua 15:63). In 18:28, Jebus appears to be a Benjamite city, whose men were also unable to drive out the Jebusites (Judges 1:21). As a result, this led to coexistence, which caused the Israelites to embrace the sins of the Jebusites (3:1–7). In David’s time, the Jebusites and Israelites probably coexisted with some kind of state of truce between them, the Jebusites controlling the city and Judah controlling the land around the city.

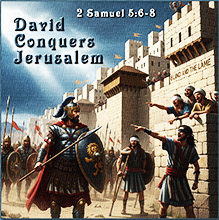

6The king and his men marched to Jerusalem to attack the Jebusites, who lived there. The Jebusites said to David, “You will not get in here; even the blind and the lame can ward you off.” They thought, “David cannot get in here” (2 Sam. 5:6).

When the people of Jebus saw David and the Israelite soldiers coming against their city, it wasn’t something new or frightening to them. Such attacks had historically occurred with some frequency, but never successfully.

Safely behind their city’s walls, the likely self-confident Jebusites mocked David and his army by bragging that they were so secure that they could turn their entire defense over to those who were blind and lame. The interchange concerning the blind and the lame (vv. 6, 8) seems to be “pre-battle verbal taunting.” The Jebusites claimed that their town was so secure that even disabled inhabitants could withstand an invasion. Another view is that the Jebusites meant that they’d fight to the last man. David countered by taking them at their word and applying “the blind and the lame” moniker to Jebusite inhabitants of Jerusalem whom he hated. “The blind and the lame” might have become a nickname for the Jebusites as a result.

In v. 8a, you can read David’s words to his men as he responded to this taunt by laying out his strategy: “Anyone who conquers the Jebusites will have to use the water shaft to reach those ‘lame and blind’ who are David’s enemies.” Ancient walled cities needed access to a water supply to survive in times of siege. Jerusalem relied on a single source, the Gihon spring, which was outside city walls, near the bottom of the Kidron Valley to the east.

Of course, we don’t know exactly how Joab and his men got into the city. David laid out the strategy, and Joab volunteered for the assignment, promising that, if he succeeded, he’d become David’s commander (1 Chronicles 11:6). We can only speculate on how the city’s fortress was entered. Perhaps they simply forced the city to surrender by cutting off its water supply. We do know that David indeed captured it. Apparently, the existing Jebusite population was neither slaughtered nor displaced as a result of this attack, because, later, David purchased a threshing floor from a Jebusite named Araunah (2 Sam. 24:18–25), on land that eventually became the site of Solomon’s temple.

Jerusalem

The city of Jerusalem is known by various names in the Bible: “Jerusalem” is the most-frequently used name; “Salem” is probably a shorthand form of “Jerusalem” (Genesis 14:18; Psalm 76:2); “Jebus” recalls the Jebusites that lived there (Josh. 18:28; Judg. 19:10–11); “Zion” refers to the stronghold taken by David (1 Kings 8:1); and “City of David” names the city after its conqueror. Joab captured this city for David from the Jebusites; from then on, people referred to it as the City of David and Zion (cf. 1 Chron. 11:4–9).

“Zion,” the popular poetic name for Jerusalem, appears more than 150 times in the Old Testament. It originally applied to the Jebusite stronghold, which became the City of David after its capture. As the city expanded to the north, encompassing Mount Moriah, the temple mount came to be called Zion (Psalm 78:68–69). Eventually the term “Zion” was used as a synonym for Jerusalem often poetically representing the city, its people, and sometimes all of Israel ( Isaiah 40:9).

“Jerusalem” (lit. “Foundation of Peace”) was an excellent choice for a capital. It stood on the border between Benjamin and Judah, so that both tribes felt they had a claim to it. It was better than Hebron in southern Judah, far from the northern tribes. Jerusalem’s elevated location, surrounded on three sides by valleys, made it fairly easy to defend. David’s choice of Jerusalem was mainly political, but the city had military advantages as well, being accessible and defensible.

As was characteristic of all the great walled cities of Canaan, Jerusalem had a vertical water shaft connected to a tunnel leading to an underground water supply outside the walls. This shaft, which is still in place today, runs about 230 feet from top to bottom. It was through this secret passage that Joab took the city.

In 1004 BC, David became king of all Israel and Judah (cf. 1 Chron. 11:1–3). The people acknowledged his previous military leadership of all Israel, as well as God's choice of him to shepherd his people as their king. Thus, David’s kingship stood on two legs: his divine election and his human recognition. We see two of the most significant events in world history in the first half of chapter 5: The first was when David became king of a united Israel. The second was when he made Jerusalem the capital of his united realm.

10And he became more and more powerful, because the Lord God Almighty was with him (2 Sam. 5:10).

The author identified the key to David’s success in v. 10. By sovereign election, the Lord chose David as his anointed. David had nothing to do with that. However, Yahweh of Israel’s armies continued to bless David because he’d related to God most properly.

† Summary of 2 Samuel 5:1–10

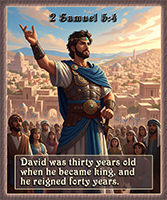

This ten-verse passage marks the unification of Israel under David’s kingship. After the death of Ish-Bosheth, all the tribes of Israel come to David at Hebron, acknowledging their kinship with him, his past leadership in battle, and God’s promise that he’d shepherd his people and be their ruler (5:1–2). In a covenant ceremony before the Lord, the elders anoint David as king over all Israel, fulfilling what had been spoken years earlier by the prophet Samuel (v. 3). David is thirty years old at the start of his reign and rules for forty years — seven and a half in Hebron over Judah, and thirty-three in Jerusalem over all Israel and Judah (vv. 4–5).

David then captures Jerusalem from the Jebusites, who’d mocked him as incapable of entering their fortified city (v. 6). Through military strategy, David takes the stronghold of Zion and makes it his capital, calling it the City of David (vv. 7–9). He builds up the surrounding areas, and the narrative emphasizes that David “became greater and greater” because the Lord Almighty was with him (v. 10). This moment establishes both the political and spiritual center for the united kingdom, with Jerusalem becoming the heart of Israel’s national and religious life.

Key points with verse references:

• All Israel’s tribes acknowledge David’s leadership and God’s calling, and make a covenant with him at Hebron (vv. 1–3).

• David is anointed king over all Israel at age thirty and reigns for forty years — first in Hebron and then in Jerusalem (vv. 4–5).

• David captures Jerusalem despite the Jebusites’ confidence in its defenses (vv. 6–7).

• The stronghold of Zion becomes “the City of David,” and David develops it as his new capital (vv. 8–9).

• David grows stronger because the Lord Almighty is with him (v. 10).

This Week’s Passage

2 Samuel 5:1–10

New International Version (NIV) [View it in a different version by clicking here; also listen to chapter 5 narrated by Max McLean.]

Summary Video: “The Second Book of Samuel”

† Watch this introductory video clip created by BibleProject on bibleproject.com.

- Q. 1 Why did the fulfillment of God’s word about David becoming king take so long?

- Q. 2 How do you evaluate David’s patience concerning this prophecy that he’d be king?

- Q. 3 How do you measure your patience regarding what you feel God has promised you?

- Q. 4 Which promises of God are you still potentially waiting to see fulfilled in your lifetime?