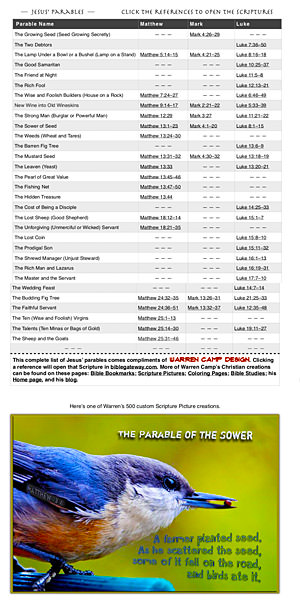

The Bible reference for Prophet Nathan’s parable, told to King David, is 2 Samuel 12:1–4. In this passage, Nathan tells David a story about a rich man who takes and kills a poor man’s single, beloved lamb, so he can provide a meal for a visiting friend. David condemns the man’s action before Nathan reveals, “You are the man.”

The Parable: Nathan tells David about a rich man with many flocks and herds who takes the only lamb owned by a poor man in town to feed a traveler.

David’s Reaction: David becomes enraged and declares the rich man is a “son of death” who is required to repay the lamb’s value fourfold (vv. 5&6).

The Revelation: Nathan then confronts David by saying, “You are the man,” applying the parable directly to David’s sin with Bathsheba and Uriah the Hittite (vv. 7–9).

† Find Warren’s short summary at the bottom of page.

Parable’s Key Word. . .

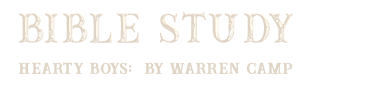

Click the list or the “bird” to enlarge and use Warren’s list of forty-four of Jesus’ parables (a PDF file with links to Scriptures).

Start Reading Warren’s Commentary . . .

Find his summary at the bottom.

par•a•ble [noun] a simple story used to illustrate the meaning of or a moral or spiritual lesson, as told by Jesus in the gospels

synonyms: allegory, moral story/tale, fable

The Parable of the Ewe Lamb

Prophet Nathan Tells It to King David

2 Samuel 12:1–4

The short parable told by the prophet Nathan to King David (12:1–4) is outstanding and special, primarily because of its masterful rhetorical strategy and the immediate, powerful impact it had on a powerful and seemingly untouchable monarch. It functions as the doorway into the entire chapter: It draws David into rendering judgment, exposes his sin, and frames the kind of justice God will apply; it then sets up the movement from sin to judgment to mercy and restoration that unfolds in the rest of the narrative. Its imagery and vocabulary quietly mirror David’s actions in chapter 11, so that once Nathan says, “You are the man,”all of chapter 12 can be read as the outworking of the parable’s moral logic in David’s real life.

Chapter 12 can be broadly divided into:

- Nathan’s parable and David’s verdict (vv. 1–6)

- Nathan’s explicit accusation and announced judgments (vv. 7–14)

- The child’s illness and death, and David’s response (vv. 15–23)

- The birth of Solomon and the resumption of royal campaigns (vv. 24–31)

The four-verse parable itself occupies only the first small section, but it sets the tone and categories — rich/poor, taking/abusing, pity/no pity, fourfold restitution, and a death-worthy offense — that are then repeated and developed in the judgments and subsequent events in David’s house.

The Parable Told by Nathan to King David

The Need for Profound Gratitude . . .

A Sincere Fear of Sinning Against Such a Gracious God

This 4-minute video highlights Nathan’s telling King David a painfully powerful parable.

The most immediate and necessary response to this parable is self-examination. It becomes a revealing mirror. Hidden beneath the royal splendor of David’s palace, Nathan’s parable of the rich man and the little ewe lamb invites every reader to step into the throne room and ask, Could I be the one God is gently, firmly confronting today?

The parable in its setting Nathan’s story doesn’t appear in a vacuum; it comes directly after David’s adultery with Bathsheba and his orchestration of Uriah’s death. Chapter 11 records how David abused his power to take another man’s wife and then arranged a cover-up that cost an innocent soldier his life. This dark backdrop makes 12:1–4 all the more striking, as the Lord sends Nathan to David with a simple, pastoral story that disarms the king’s defenses before exposing his heart.

Nathan Rebukes David

12 1The Lord sent Nathan to David. When he came to him, he said, “There were two men in a certain town, one rich and the other poor. 2The rich man had a very large number of sheep and cattle, 3but the poor man had nothing except one little ewe lamb he had bought. He raised it, and it grew up with him and his children. It shared his food, drank from his cup and even slept in his arms. It was like a daughter to him.

4“Now a traveler came to the rich man, but the rich man refrained from taking one of his own sheep or cattle to prepare a meal for the traveler who had come to him. Instead, he took the ewe lamb that belonged to the poor man and prepared it for the one who had come to him” (2 Sam. 12:1–4).

The parable itself is straightforward: a rich man with many flocks steals the single beloved ewe lamb of a poor man to feed a traveler, instead of slaughtering one of his own animals. The lamb isn’t just property; it’s treated like a family member, sharing food, drink, and affection in the poor man’s household, underscoring the cruelty of the rich man’s act.

Exposing sin through holy imagination Nathan’s use of a parable documents God’s kindness and wisdom in confronting sin. Rather than accusing David outright, Nathan invites him to step into someone else’s story and feel righteous anger at injustice. When David burns with anger and declares that the rich man deserves to die and must restore fourfold, he unknowingly pronounces judgment on himself. The next two verses (vv. 5–6) capture this moment of moral clarity before the truth lands.

5David burned with anger against the man and said to Nathan, “As surely as the Lord lives, the man who did this must die! 6He must pay for that lamb four times over, because he did such a thing and had no pity” (2 Sam. 12:5–6).

This pattern appears often in Scripture: God uses stories, images, and questions to help people see themselves truly. Jesus would later employ parables in a similar way to uncover the hearts of his hearers, for example, The Parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37) and The Parable of the Wicked Trustees/Tenants (Matthew 21:33–43). The Spirit still uses Scripture’s narratives today to bypass our self-justification and let us react honestly to sin before revealing, “This is what your heart looks like.”

7Then Nathan said to David, “You are the man! This is what the Lord, the God of Israel, says: ‘I anointed you king over Israel, and I delivered you from the hand of Saul. 8I gave your master’s house to you, and your master’s wives into your arms. I gave you all Israel and Judah. And if all this had been too little, I would have given you even more. 9Why did you despise the word of the Lord by doing what is evil in his eyes? You struck down Uriah the Hittite with the sword and took his wife to be your own. You killed him with the sword of the Ammonites” (2 Sam. 12:7–9).

“You are the man”: the shock of recognition The turning point comes when Nathan declares, “You are the man!” and then speaks the Lord’s words of indictment. Verses 7–9 remind David of everything God graciously gave him — kingship, deliverance from Saul, his master’s house, the kingdoms of Israel and Judah — before asking why he despised the word of the Lord by taking Uriah’s wife and arranging his death.

This contrast between grace and ingratitude is central. David isn’t a random sinner; he’s a deeply blessed man who used God-given power to satisfy his desires at terrible cost to others. The rich man in the parable is thus a mirror for David: abundance twisted into entitlement, authority turned into oppression, desire elevated above obedience. James 1:14–15 echoes this dynamic, showing how unchecked desire leads to sin and eventually death.

Consequences and mercy intertwined Nathan goes on to announce sobering consequences: the sword won’t depart from David’s house, evil will arise from his own family, and what he did in secret will be answered by public humiliation. Verses 10–12 set out this pattern of discipline, which plays out later in David’s life through family conflict, rebellion, and grief.

10“Now, therefore, the sword will never depart from your house, because you despised me and took the wife of Uriah the Hittite to be your own.’ 11“This is what the Lord says: ‘Out of your own household I am going to bring calamity on you. Before your very eyes I will take your wives and give them to one who is close to you, and he will sleep with your wives in broad daylight. 12You did it in secret, but I will do this thing in broad daylight before all Israel.’” 13Then David said to Nathan, “I have sinned against the Lord.”

Nathan replied, “The Lord has taken away your sin. You are not going to die (2 Sam. 12:10–13).

Yet even in judgment there’s mercy. When David finally confesses, “I have sinned against the Lord,” Nathan answers, “The Lord has taken away your sin. You are not going to die” (v. 13). That single verse is indeed one of the most powerful displays of divine mercy in the Old Testament, showcasing how God’s grace instantly meets genuine confession, even for the most grievous sins.

Psalm 51 (shown here) is traditionally linked to this moment of repentance, giving a window into David’s broken and contrite heart. God forgives David personally, but some earthly consequences remain — most painfully, the death of the child born to Bathsheba (vv. 14–18). This pairing of forgiveness with discipline reflects Hebrews 12:5–11, where the Lord’s chastening is presented as loving fatherly correction, not cold punishment.

14“But because by doing this you have shown utter contempt for the Lord, the son born to you will die.”

15After Nathan had gone home, the Lord struck the child that Uriah’s wife had borne to David, and he became ill. 16David pleaded with God for the child. He fasted and spent the nights lying in sackcloth on the ground. 17The elders of his household stood beside him to get him up from the ground, but he refused, and he would not eat any food with them.

18On the seventh day the child died. David’s attendants were afraid to tell him that the child was dead, for they thought, “While the child was still living, he wouldn’t listen to us when we spoke to him. How can we now tell him the child is dead? He may do something desperate” (2 Sam. 12:14–18).

The text goes on from vv. 19–31, highlighting these follow-up accounts: The child of David and Bathsheba dies (vv. 15–23), the birth of King Solomon (vv. 24, 25), and David and Joab conquer Rabbah (vv. 26–31.

Personal application: when Scripture points at us Nathan’s parable reminds every believer that spiritual blindness is real; even a man after God’s own heart (1 Samuel 13:14) can justify shocking sin when unconfessed desire takes root. The story invites two honest questions: (1) Where has God been abundantly gracious, yet gratitude has cooled into entitlement?... (2) Are there people being treated as expendable in order to protect reputation, comfort, or secret sin?

Like David, many only see their actions clearly when Scripture confronts them indirectly — through a sermon, a story, or a passage that suddenly feels uncomfortably specific. Hebrews 4:12 describes God’s word as living, active, and piercing, able to discern the thoughts and intentions of the heart; Nathan’s parable is a vivid example of that living word at work.

Responding like David, not the rich man The hope of this passage lies not in David’s goodness but his response once exposed. He doesn’t argue, blame others, or minimize his actions. Instead, he confesses, accepts God’s verdict, fasts, and worships, even when the child dies (vv. 13–23). His path forward models genuine repentance, as shown here:

• Acknowledging sin primarily as an offense against the Lord (Psalm 51:4).

• Owning the consequences without bitterness.

• Returning to worship and obedience rather than retreating in shame.

For believers, this points to Jesus Christ, the true Son of David, who bore the ultimate consequence of sin on the cross so that repentant sinners can be fully forgiven (2 Corinthians 5:21; Romans 8:1). David’s spared life anticipates the greater mercy available in Christ, where confession is met not only with discipline but with cleansing and restored fellowship (1 John 1:9).

An invitation to let the story read you Nathan’s parable is more than an ancient moral tale; it’s an invitation to let God’s Spirit step into the “throne room” of your own heart. Rather than reading it at arm’s length as “David’s shameful episode,” receive it as a gracious confrontation from a God who loves too much to leave sin hidden. When the word of God says, “You are the man” or “You are the woman,” it’s never meant to destroy! Instead, it’s to bring into the light what Christ is willing to forgive, heal, and transform.

The Timeless Lesson

David’s experience teaches that there is immediate, total spiritual forgiveness for any sin — no matter how monstrous — upon genuine confession. However, it simultaneously warns that sin has real, earthly ripple effects that may continue to cause pain and loss, long after the sin itself is forgiven.

This tension between God’s unfailing grace and his sovereign justice is the enduring power of this parable’s passage. It compels a response of profound gratitude and a sincere fear of sinning against such a gracious God.

What Makes Nathan’s Parable Special? The parable, which tells of a rich man with many flocks who unjustly steals and slaughters a poor man’s single, cherished ewe lamb, is remarkable for several reasons:

• Subtle Confrontation of Power: Nathan’s approach is a brilliant act of “speaking truth to power.” David, as an absolute king, could have easily silenced or executed anyone who directly accused him of his sins — adultery with Bathsheba and the murder of her husband, Uriah. By using a seemingly fictional story of social injustice, Nathan skillfully lowers David’s defenses.

• Self-Condemnation: The parable is designed as a moral trap. It appeals to David’s own deeply ingrained sense of justice, especially as a former shepherd and a king expected to protect the weak. David becomes so outraged by the fictional rich man’s greed and cruelty that he pronounces a harsh sentence, unknowingly condemning his own actions.

• The Climactic Line: The power of the story culminates in the piercing, four-word declaration: “You are the man!” (v. 7). This dramatic and sudden application of the allegory forces David to see the gravity of his sin from an objective, moral standpoint, leading to immediate repentance.

• Focus on Injustice and Greed: The parable focuses on greed and the exploitation of the vulnerable, which provides a powerful moral lens for David’s actions. He, who had abundant resources (many wives, wealth, power), took the one precious possession (Uriah’s wife, Bathsheba) from a loyal, less powerful man (Uriah).

Relevance in Today’s World

Nathan’s parable remains highly relevant today as a timeless lesson in ethical leadership, social justice, and personal accountability.

1. The Principle of Speaking Truth to Power... The story serves as a blueprint for how to hold the powerful accountable:

• Courageous Communication: Nathan’s example inspires individuals, including journalists, activists, and advisors, to find effective, tactful, and courageous ways to deliver difficult truths to those in positions of authority, even when personal risk is involved.

• Bypassing Defenses: The method of using an analogy or story to let a person discover their own wrongdoing, rather than starting with a direct accusation, is a timeless strategy in effective and non-confrontational communication, applicable in corporate, political, or personal settings.

2. Social and Economic Justice... The core of the parable is a profound condemnation of economic and power disparity:

• Exploitation of the Weak: The rich man who, despite his abundance, takes the only valuable thing from the poor man, is a clear metaphor for modern-day corporate greed, systemic injustice, and the exploitation of marginalized groups by the wealthy and powerful.

• Empathy for the Marginalized: The vivid description of the poor man’s deep, almost familial relationship with his single lamb — it ate from his table, drank from his cup — forces the listener to empathize with the profound loss of the vulnerable. This highlights the biblical mandate to protect those who have little.

3. Personal Accountability and Repentance... The parable emphasizes that power and privilege don’t negate moral law:

• No One Is Above the Law: It affirms the principle that even the most powerful leaders are accountable to a higher moral standard (or divine law). This concept is fundamental to the rule of law in modern democracies.

• The Need for “Nathans”: We all have blind spots in our lives, especially when we are accustomed to power or comfort. The story stresses the importance of having trusted “Nathans” — friends, mentors, or internal checks — who are willing to tell us the hard truth and challenge us to self-reflect and repent when we stray.

He raised [the ewe lamb], and it grew up with him and his children. It shared his food, drank from his cup and even slept in his arms. It was like a daughter to him (2 Sam. 12:3b).

Take our “Parables Quiz.”

See Warren’s other “Parables of Jesus” commentaries.

— Warren’s Concise Summary —

The Parable of the Ewe Lamb, told by the prophet Nathan to King David in 2 Samuel 12:1–4, describes a rich man who owns many sheep and cattle, and a poor man who has only one little ewe lamb, which he loves like a daughter. When a traveler comes to the rich man, instead of using one of his own animals, the rich man takes the poor man’s beloved lamb and prepares it for his guest. Nathan tells this story to confront David about his sin with Bathsheba and the murder of her husband Uriah; David, moved by the injustice, pronounces judgment on the rich man, only to hear Nathan say, “You are the man,” revealing that David’s actions mirror the rich man’s cruelty.

The parable powerfully exposes David’s guilt, leading him to repentance, teaching that God uses stories to awaken conscience and call people to accountability for their actions.