This parable is a natural follow-up to the Parable of the Wise Manager (or Unjust Steward). If that parable teaches how riches are to be used, this parable sets forth the terrible consequences of the failure to use them.

In the Rich Man and Lazarus, Jesus teaches that heaven and hell are both real, literal places. It also illustrates the reality that, once we cross the eternal horizon, that’s it; there’ll be no more opportunities to choose.

Incidentally, Jesus spoke about the heaven-or-hell judgment more than anyone else in the Bible and in a very specific way. More than half of the parables that Jesus told relate to God’s eternal judgment of sinners.

† Find Warren’s short summary at the bottom of page.

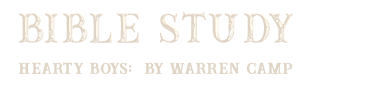

Click the list or the “bird” to enlarge and use Warren’s list of forty-four of Jesus’ parables (a PDF file with links to Scriptures).

Start Reading Warren’s Commentary . . .

Find his summary at the bottom.

par•a•ble [noun] a simple story used to illustrate the meaning of or a moral or spiritual lesson, as told by Jesus in the gospels

synonyms: allegory, moral story/tale, fable

Jesus’ Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus

Luke 16:19–31

Jesus has been teaching about materialism and money. His audience included his disciples (16:1), as well as the “Pharisees, who loved money” so he ridiculed their stand on money (16:14). Jesus affirmed the validity of the Law, rightly interpreting it (16:16–18), which was important to the Pharisees. This fourth and final “judgment” parable condemns the Pharisees for their love of money and their neglect of showing compassion for the poor (vv. 19–31).

Before we dig into the meaning and purpose of this parable, it’s appropriate to first consider to whom Jesus was speaking in his Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus. With which category of people was he dealing? The last verse prior to Jesus’ recitation (v. 14) says, “The Pharisees, who loved money, heard all this and were sneering at Jesus.” They were a class of men who were notorious throughout the gospels for their refusal to deal honestly with him and the truths that he taught.

We can be sure that of all the people whom Jesus taught, none were handled more guardedly than the wily Pharisees. They dealt in deception and subterfuge, while Jesus dealt with them wisely and truthfully. The safest way for Jesus to communicate with the Pharisees was by parable and allegory, as clearly shown in this summary’s video clip.

Video compliments of Crown Financial Ministries, with a 40-second intro

Today, people struggle to illuminate certain parables, often getting lost in the details. The Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus is an excellent example of a teaching of Lord Jesus that has generated a lot of discussions, head-scratching, and interpretations. Let’s take a look at this challenging parable.

The Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus

A Parable of Judgment

In this parable, a rich man who passes away finds himself in Hades, a place of eternal punishment, while a beggar named Lazarus ends up in a place of comfort, next to Abraham —it’s a complete reversal of one another’s circumstances from when they were alive. After dying, the rich man realized that the choices he made in life eventually brought him to a place of permanent agony. He also realized that his brothers, still alive on earth, had a chance to avoid that fate. So he begged Abraham to send someone back to warn them.

That’s it — a simple story about two people and what happened after they died.

We’ll first set the stage for this teaching. Luke 15 begins with some Pharisees and lawyers mingling in a crowd in which Jesus has been teaching. They instantly criticize him over the fact that he was known to deliberately spend time with sinners. Jesus responded by launching into a number of parables: the Lost Sheep, Lost Coin, Lost (or Prodigal) Son, and Shrewd Manager. When he spoke the last parable, which touches on how we use our money and resources, Luke tells us that the “The Pharisees, who loved money, heard all this and were sneering at Jesus” (16:14). It’s this tense exchange that sets the stage for Jesus’ story about Lazarus and the rich man.

Jesus begins by introducing us to two characters: an extremely wealthy man and a beggar named Lazarus. Interpreters often get caught up in the fact that this is the only parable in which Jesus names any of the central characters. Because of this, there’s a tendency to attach greater significance and meaning to this parable than to others.

Who was this parable’s symbolic rich man? The Jews had been blessed above measure by a knowledge of God and his plan of salvation for all mankind. Only a Jew would pray to “Father Abraham,” as we find the rich man doing later in this story. The Jewish nation was clearly represented by such a character as this. And, to the rich man, Lazarus was just another face in the crowd, an invisible poor person who disappeared into the background of this rich man’s comfortable, lavish life. But in the afterlife, the first has become last. Jesus wants to give us a solid understanding of this great reversal. When all is said and done, this rich man became nameless; it’s Lazarus whose name continues to be remembered.

While the rich man represents the Jewish nation, Lazarus symbolizes all those people in spiritual poverty — the non-Jewish Gentiles — with whom the Israelites were to share their heritage. Unfortunately, the Jews hadn’t shared any of their spiritual wealth with the Gentiles. Instead, they considered them “dogs” that would have to be satisfied with the spiritual crumbs that occasionally fell from their masters’ tables. The rich Jews had hoarded the truth; doing so they’d corrupted themselves. Only moments before relating this parable, Jesus had rebuked the Pharisees for their spiritual conceit.

The Jews had enjoyed “the good life” while on earth but had done nothing to bless or enrich their neighbors. No further reward was due them: “But woe to you who are rich, for you have already received your comfort. Woe to you who are well fed now, for you will go hungry. Woe to you who laugh now, for you will mourn and weep” (6:24–25). Conversely, the poor in spirit, symbolized by Lazarus, would inherit the kingdom of heaven. The Gentiles who hungered and thirsted for righteousness would be filled. The “dogs” and sinners, so despised by the self-righteous Pharisees, would enter heaven before they would (Matthew 21:31).

The Setting of This Drama (vv. 22–28)

Next, we’re introduced to the conflict in this story. But we have to be very careful — it’s incredibly easy to get lost in the details. The point of this story isn’t necessarily to describe particulars about the afterlife. If it were, we’d have to assume that those in heaven can watch and interact with sufferers in Hades — which doesn’t make it sound much like paradise.

The New International Version (NIV) tells us that the beggar was carried to Abraham’s side; others say “the bosom of Abraham.” The Jews saw Abraham, the patriarch of Israel, as the gatekeeper to the afterlife. First-century Hebrews thought of him in the same way we talk about Peter being heaven’s sentry. It makes sense that Jesus would invoke this imagery for his specific listeners.

The parable concludes with the rich man begging that his brethren be warned against sharing his fate. Asking Abraham to send Lazarus on this mission, he alleges “but if someone from the dead goes to them, they will repent” (v. 30). Abraham replied, “If they do not listen to Moses and the Prophets, they will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead” (v. 31). Jesus thus rebuked the Pharisees for their disregard of the Scriptures, foreseeing that even a supernatural event would not change the hearts of those who persistently rejected the teachings of “Moses and the Prophets.”

It’s essential that we draw our attention to two elements of this story:

- The rich man’s sin: There’s never any indication of any abuse or mistreatment aimed at Lazarus. Abraham merely points out that the rich man lived in comfort while Lazarus was tormented, and now the roles are reversed. If there is any sin here, it’s the fact that the rich man ignored Lazarus. He wasn’t wicked to Lazarus; he was indifferent.

- The rich man’s arrogance: It’s almost comical that in this new situation, the rich man ignores Lazarus to address Abraham. In fact, as far as the rich man is concerned, Lazarus is still a prop — someone with no influence of his own. He wants Abraham to send Lazarus to him to quench his thirst. And when Abraham declines, he asks for Lazarus to be sent to his family with an advisory warning.

Profiles of the Rich Man and Lazarus

Looking carefully at the text of this parable, we start with its two opening verses.

“There was a rich man who was dressed in purple and fine linen and lived in luxury every day. 20At his gate was laid a beggar named Lazarus, covered with sores and longing to eat what fell from the rich man’s table. Even the dogs came and licked his sores” (vv. 19–21).

Jesus paints a quick portrait of the rich man; a very, very rich man. Purple dye was extremely expensive; a purple wool mantle or cloak was costly; a finely-woven linen tunic was considered the height of luxury. The mention of these garments and of a continual banqueting indicates a life of extreme luxury. (Be sure to watch these highlights in the video above.)

Jesus contrasts the rich man with a beggar, the poorest of the poor. The beggar’s name is Lazarus, the only character in any of Jesus’ parables who is given a name. Lazarus is short for Eleazar, which means “He (whom) God helps.” The name is symbolic of destitution; many words indicative of beggary are derived from it. In the last stages of life, Lazarus had become an object of charity while the rich man gave him nothing.

There’s nothing to indicate that he’d been an habitual beggar. Lying at a suitable place for begging, next to the rich man’s gate, probably placed there by friends, Lazarus is sick, as evidenced by his numerous ulcerated sores. And he’s hungry, longing to eat the scraps from the rich man’s table, usually reserved for the dogs. The dogs that lick his sores are not pets. (Got the picture?)

Enter Abraham

“The time came when the beggar died and the angels carried him to Abraham’s side. The rich man also died and was buried” (v. 22).

Jesus next portrays angels carrying Lazarus to Abraham. This puts Lazarus in the place of honor at the right hand of Abraham at the banquet in the next world. The poor man’s values are miraculously reversed. The rich man passed from view with the pomp and pageantry of a burial, an earthly honor suited to a worldly life. But Lazarus passed away, among angels, a spiritual triumph suited to one accepted of God.

The Tormented Rich Man

“In Hades, where he was in torment, he looked up and saw Abraham far away, with Lazarus by his side. 24So he called to him, ‘Father Abraham, have pity on me and send Lazarus to dip the tip of his finger in water and cool my tongue, because I am in agony in this fire’” (vv. 23–24).

Hades (Greek) or Sheol (Hebrew) was the name given to the abode of the dead, between death and the resurrection. The rich man, having called out to Father Abraham as one of his kindred, also experienced a reversal. He was in “hell.” This torment in Greek is basanos, “severe pain occasioned by punitive torture.” Parched with thirst, his tongue was hot and dry; indeed, he was suffering. The Greek verb used here is odunao, “to undergo physical torment, ‘suffer pain.’” The source of the suffering is a lake of fire.

What higher honor or joy could the Jew conceive of than finding himself in such a condition of intimacy and fellowship with Abraham, the great founder of their race? The smallness of the requested favor indicated the greatness of the distress, as it does in v. 21, where crumbs were desired. There’s a reciprocity also between the desired crumbs and the prayed-for drop.

The friendship of Lazarus might have been easily won, and now the rich man needed that friendship, but he’d neglected the principle set forth in v. 9, and had abused his stewardship by wasting his substances upon himself. Again, the former condition of each party is sharply reversed. Lazarus feasts at a better banquet, and the rich man begs because of a more dire and insatiable craving. Thus the life despised of men was honored by God, and (v. 15) the man who was exalted among men is found to have been abominable unto God.

A Great Impassable Chasm

Father Abraham explained the situation, describing a great, impassable chasm (Greek chasma) that prevents anyone from passing from one side to another. In other words, there was no hope of moving from torment to the blessings of Abraham’s bosom — or of Lazarus helping the rich man. The die had been cast; the outcome was irreversible.

“But Abraham replied, ‘Son, remember that in your lifetime you received your good things, while Lazarus received bad things, but now he is comforted here and you are in agony. 26And besides all this, between us and you a great chasm has been set in place, so that those who want to go from here to you cannot, nor can anyone cross over from there to us’” (vv. 25–26).

The rich man had the stewardship responsibilities of wealth, with its accompanying obligation to be generous. It was that obligation that he’d esteemed as too contemptibly small to deserve his notice. But in neglecting it, he’d inadvertently been unfaithful in much. This had been the rich man’s sin of omission; his sin of commission answered as a complement to it, for he’d been guilty of the money-loving self-indulgence that was condemned by Jesus, yet justified by the Pharisees (vv. 14–15). No other crime was charged against the rich man, yet he suffered torment. During his lifetime, he’d been so deceived by his wealth that he’d failed to detect his sin. Moreover, as he indicates in v. 28 (shown below), a like deception was now being practiced upon his brothers. Thus the parable justifies the term “unrighteousness.”

Regarding the great chasm or gulf, we see here a clear picture of the separation that parts good people from evil people in the future state. Ironically, the chasm or gulf of “pride and caste” between the rich man and Lazarus, while on earth, was and is an easy one to cross.

God’s Word — The Sufficient Warning

Jesus concludes his parable in a curious way. The rich man wanted Lazarus to warn his five brothers of the dangers of hell. But Abraham told the rich man that, if his brothers wouldn’t heed the truth that they’d already had learned — from Moses and the Prophets (i.e., the Old Testament revelation) — they certainly wouldn’t consider believing something coming from someone who’d rise from the dead.

“He answered, ‘Then I beg you, father, send Lazarus to my family, 28for I have five brothers. Let him warn them, so that they will not also come to this place of torment.’

29“Abraham replied, ‘They have Moses and the Prophets; let them listen to them.’

30“‘No, father Abraham,’ he said, ‘but if someone from the dead goes to them, they will repent.’

31“He said to him, ‘If they do not listen to Moses and the Prophets, they will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead’” (vv. 27–31).

Here, the rich man proposed that Lazarus would rise from the dead so he could serve the rich man by warning his brothers. The two attempts of the rich man to use Lazarus as his servant show how hard it was for him to adjust himself to his new irreversible condition. But Luke’s readers would have immediately thought of Jesus, and how even his unmistakable resurrection wasn’t enough to sway the Pharisees from their hardened opposition to the truth that was clearly before them.

Verse 28 clearly documents that, deceived by his wealth, the rich man still looked upon his earthly possessions as real, substantial, and accessible. Like rich sinners today, he’d simply disregarded the affairs of the future life. Aroused by the sudden experience of the awful realities of the future state in which he now abided eternally, he desired to make it as real to his brothers as it had now become to him. I don’t believe that his concern for his brothers was told by Jesus in order to indicate repentance. More likely, it was mentioned to raise the point of the revealed will of God: It is inexcusable for man to lead a selfish life.

When Abraham said, “They have Moses and the Prophets” (v. 29), he emphasized that the Scriptures are a sufficient guide to godliness and that a failure to live rightly when in possession of them was due to a lack of will, not to a lack of knowledge. And, in v. 30, it’s interesting to see that the rich man, having had the spirit of a true Pharisee, appealed to Abraham for a life-saving sign to be given to his brothers. He failed to realize and appreciate that the guidance in the Scriptures was better than any earthly sign.

In Jesus’ closing verse, his “if someone rises from the dead” should have reminded the rich man of the fact that Jesus had already raised at least two people from the dead: (1) The widow of Nain’s son (Luke 7:11–17 and (2) the miraculous raising of Jairus' daughter. Jairus’ daughter (Luke 8:52–56). As such, he’d have known well of Jesus’ divine power. And he’d now personally seen him raise a third person who, with startling suggestiveness, had the very name “Lazarus” (John 11). But despite having witnessed Jesus’ resurrection of the widow’s son and Jairus’ daughter, the majority of the Jews disbelieved and continued to disbelieve in him. Sadly, they even went so far as to seek the death of Lazarus that they might be rid of his testimony (John 12:9–10).

I think that these are Jesus’ two main points in his Rich Man and Lazarus Parable.

1. Wealth without active mercy for the poor is great wickedness.

2. If we close our eyes to the truth that we’re given, we’re doomed.

A Hearty Way to Apply This Parable Today

When we’re looking at a parable, the first question we need to ask is, “What was Jesus saying to the original listeners?” In this case, we have to consider what the message was to the Pharisees. On the surface, Jesus was addressing their love of money. No one knew the Law and the Prophets like the Pharisees. The Law hadn’t rectified the way they thought about money. To them, money bought influence, power, and comfort. They didn’t consider it a resource that God intended them to share with those in need — even though Scriptures told them otherwise.

But Jesus is making a broader point about the nature of spiritual blindness. The rich man’s brothers wouldn’t believe because they’d remained unwilling to believe. It doesn’t matter who delivered the message; their hearts were committed to disobedience, having found ways to justify their lifestyle and rebelliousness.

Jesus is also making the pointed accusation that the Pharisees were doing the same with him. Although Jewish Scriptures point to Jesus as the Messiah, they refused to see and accept it. He told the Pharisees elsewhere, “You study the Scriptures diligently because you think that in them you have eternal life. These are the very Scriptures that testify about me, yet you refuse to come to me to have life” (John 5:39–40). Eventually, Jesus rose from the grave, yet they still chose not to believe.

As Christ’s disciples, we must ask ourselves:

Q. What are we to learn from this parable? Jesus: What are you saying to us today?

A. In a sense, the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus teaches a lesson similar to that of what I highlight in my commentary on The Shrewd Manager (or Unjust Steward) Parable (16:1–13). We can use our money to secure for us “eternal damnation” or “friends in heaven who will welcome us.” The choice is ours.

You can see a similar lesson taught in another parable dealing with “judgment”: Matthew’s portrayal of The Sheep and the Goats Parable.

The moral of the story: The rich man asked Abraham to send Lazarus back to warn his brothers so they wouldn’t suffer the same fate, but Abraham refused. He told the rich man that they had the testimony of Moses and the Prophets to warn them but hadn’t heeded those wise words. May we never neglect to heed the Word of God!

But what if someone comes back from the dead? The rich man ignored Abraham’s words. He pointed out that if someone were to come back from the dead, his brothers would then pay attention. But Abraham told the man that if his brothers hadn’t listened to the prophecies of Moses and the Prophets, they wouldn’t pay attention to someone who’d been resurrected. Clearly, Jesus was alluding to the fact that He will rise from the dead. Such an incredible act would confirm everything that Jesus had taught and said; sadly, most of the chief priests and Pharisees didn’t listen to or accept Lord Jesus’ teaching or divine accomplishments. As soon as Jesus’ buried body became missing, the chief priests paid off the guards and told them, “You are to say, ‘His disciples came during the night and stole him away while we were asleep.’ If this report gets to the governor, we will satisfy him and keep you out of trouble” (Matthew 28:13–14).

Abraham made the point to the rich man that those Jews who ignored Moses and the Prophets wouldn’t somehow be swayed by a miraculous messenger. After all, the entire Law of Moses is built upon amazing messages from miraculous messengers.

Wealth is not bad! After all, Abraham was wealthy. But wealth brings with it certain responsibilities, namely stewardship. We’ll eventually give an accounting of how we handled the wealth that God has given us and asked us to manage for him. Fortunately, we still have time to improve our stewardship account with God.

Obviously, the surface level point about not ignoring those who are suffering while we live in luxury is apt. Most folks in the West live lavish lifestyles that would surprise first-century rich people. Those who follow Jesus and consider Scripture to be an authority in their life need to be serious about sacrificial and generous giving. On top of that, we need to wrestle with this parable’s larger point: It’s critical that we act on the truth that we know.

There are many scriptural teachings that we excuse ourselves from taking seriously. Maybe it’s because we pretend not to really understand them or we tell ourselves that we need just a little more information and clarification before we obey. It could be that we know it’s something we need to work on so we promise ourselves that we’ll do so later.

Alas, a lot of that self-talk is intended to be a means of postponing and avoiding what we know we should do. But there’s coming a time when we’ll be accountable for what we did with the information we had. We won’t be able to plead ignorance or claim not to have understood the Lord’s expectations. Jesus is encouraging his listeners of this parable to do some self-examination. And as James reminds us, we can’t “merely listen to the word, and so deceive [ourselves].” We have to “do what it says” (James 1:22).

We Bible-toting, hearty Christians have the benefit of the Old and New Testaments. If we don’t see, recognize, and minister to the poor on a regular and measurable basis, we’ll have no justifiable excuse to give Jesus at judgment time. In the final analysis, a rich man’s punishment is not due for having owned riches; it’s for neglecting the Scriptures and what they teach us about our need to responsibly care for and generously support those in need.

Just as the rich man desperately pleaded for someone to warn his family, so believers should also sense the urgency to share the good news of Jesus Christ with those who haven’t yet heard or understood Jesus’ gospel account. After all, there’s an eternal reward for those who believe the gospel message and follow the teachings of Jesus; and there’s eternal punishment for those who don’t.

Question 1 Whom do you resemble more closely: the rich man and his brothers? Lazarus? Why so?

Question 2 Since lack of knowledge isn’t the brothers’s problem, what is? How do you see that tendency in yourself?

Question 3 How do you feel about discussing Judgment Day with friends? With strangers? Are you ready to discuss it.

“But Abraham replied, ‘Son, remember that in your lifetime you received your good things, while Lazarus received bad things, but now he is comforted here and you are in agony’” (Luke 16:25).

Take our “Parables Quiz.”

See Warren’s other “Parables of Jesus” commentaries.

— Warren’s Concise Summary —

Jesus’ Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus contrasts a nameless rich man, who lives in luxury and ignores a poor, sore-covered beggar named Lazarus, lying at his gate, with their reversed situations after death. Lazarus is carried to Abraham’s side in comfort, while the rich man finds himself in torment in Hades, separated from relief by a great chasm and unable to receive even a drop of water.

When the rich man begs that Lazarus be sent to warn his brothers, Abraham replies that they already have Moses and the Prophets and that those who won’t listen to them won’t be convinced even if someone rises from the dead, underscoring that neglect of the needy, false security in wealth, and refusal to heed God’s word bring irreversible judgment, while faithful sufferers are ultimately comforted by God.